Agentic Software

Agentic Systems

AI Agents

Agentic Systems: What They Are and What’s Inside

If you think an agent is just “LLMs + tools,” you’re already in trouble. Autonomy has costs. Context has limits. And most problems don’t need agents at all. This is a no-bullshit guide to agentic systems—for people who actually plan to deploy them.

Introduction

ChatGPT launched on November 30, 2022 and hit 100 million users in two months making it the fastest-growing consumer app ever. Since then, AI has fundamentally changed how software—and increasingly entire businesses—are built.

And to put things into perspective: MCP (Model Context Protocol) went public only a year ago (November 2024) and it’s already one of the hottest topics in software. Everyone’s heard about this annoying “USB-C for LLMs” trope—a unifying interface for tools, data, and prompts.

At the same time, we’re seeing a shift in applications themselves: NPCs that actually listen and react, instead of repeating scripted dialogue.

Creating apps from a single prompt. Debugging complex code without documentation. Automating DevOps tasks. Planning trips. Writing marketing materials. Generating video, images, music; the list goes on.

Analytics through conversation—no SQL, no analyst.

Video generated on the fly for a specific context.

All of this was impossibly complex just a couple of years ago. Not because it was expensive — but because every edge-case required another “if-else” block. Every new scenario required new code.

Agents change the rules: give them a goal and the right tools, and they’ll figure out the rest themselves.

In this article, we’ll cover:

What an agentic system actually is

How agents are built in practice

How autonomy scales from simple functions to full systems

How agents interact with their environments

What agents can actually do

When not to use an agent

Implementation considerations

Real-world examples

What’s next

What The Hell is an Agentic System: Taxonomy

AI—well, an LLM specifically—is like a brain in a jar. Literally, an intellectual unit: no will, no aspirations. Useless, until it receives a stimulus from the outside: a human message, a cron trigger, an event. Like your questions about throwing a uranium crowbar into mercury (it’ll sink, but try a steel anvil instead).

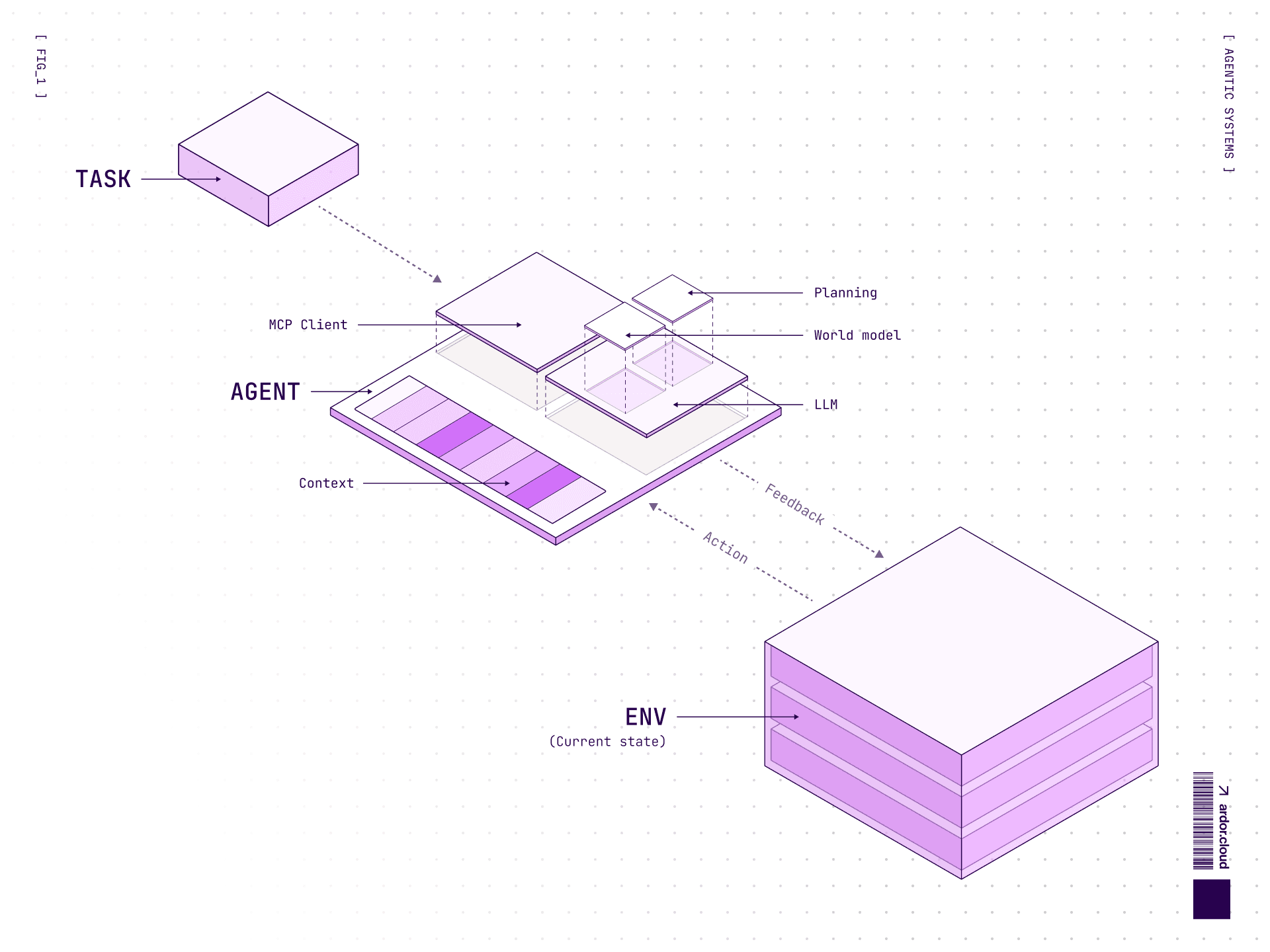

More formally—an agentic system or AI agent is a software with some level of autonomy based on an LLM that can understand context (not just text, but any data depending on what modalities the model was trained on) and use tools to get information from the environment and change its state based on feedback.

Taxonomy: How to Think About This

Some think about agents as fully autonomous systems that operate independently over extended periods, using various tools to accomplish complex tasks.

Others use the term to describe more prescriptive implementations that follow predefined workflows.

Anthropic has a good proposal. They categorize everything as “agentic systems” and split by architecture:

Workflows: LLMs and tools orchestrated through predefined code paths. You control the path, LLM fills in the blanks. Like a flowchart that became sentient but still respects the arrows.

Agents: LLMs dynamically direct their own processes and tool usage. You give it a goal and tools, it figures out the steps. Might take 3 steps, might take 30. You’re not directing anymore—you’re supervising.

Both are “agentic systems”. But workflows are predictable and debuggable. Agents are flexible, but difficult to debug in practice. Choose based on how much you trust the model, and whether you need predictable consistency or autonomous decision-making.

I like this architectural distinction.

But based on what we build and what we’ve seen our users do, I find a more practical taxonomy—one organized by complexity and autonomy—more useful:

AI Function → Workflow → Assistant → Agent → Agentic System

This spectrum goes from “do this one thing” to “figure it out yourself”.

We'll break down each level after covering the architectural basics.

Types by Autonomy Level

Not all agents are created equal. They exist on a spectrum.

Simple reactive agents: Act exclusively in response to user request. Can’t initiate dialogue, don’t save history, each interaction starts from clean slate. Think of a simple chatbot that forgets everything the moment you close the tab.

Semi-autonomous agents: Can analyze data in real-time without constant human requests. Might monitor systems, detect anomalies, prepare reports. But still need human approval for actions.

Learning agents: Can accumulate data and save it for reuse—through in-context learning or external memory (like Cursor rules, claude.md/ardor.md, or custom system files). They don’t change model weights, but they remember what worked. Current SWE agents are moving in this direction.

Multi-agent systems: Multiple specialized agents working together. Why? Specialization and division of labor. If you stuff everything into one agent its prompt becomes dimensionless and its quality suffers. Fair warning: multi-agent systems are currently complex and fragile. Resort to them only when you’ve exhausted single-agent possibilities.

How Agents Are Built: Architecture

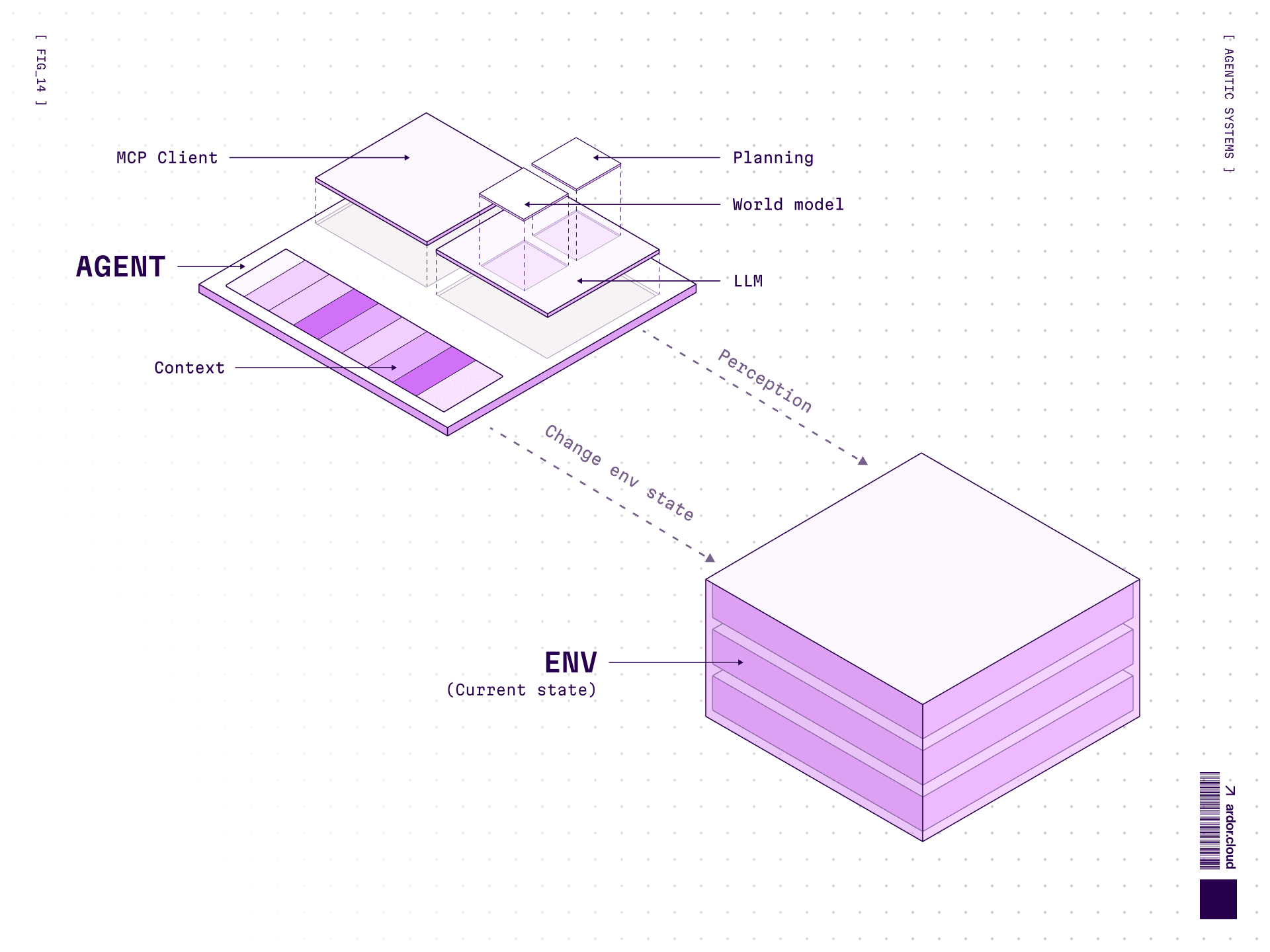

At the core of every agentic system lies at least one model and a set of tools for interacting with the environment. In simple terms, an agent can perform two actions:

Act: Generate tool calls to interact with its environment, get feedback, perform actions, etc.

Reason: Analyze data, detect patterns, plan next steps, etc.

Models can think, but they don’t remember between calls. Each iteration starts afresh. If you need persistent planning (multi-step tasks), you need mechanisms to keep the plan in context—scratchpad, chain-of-thought in conversation history, or explicit memory tools.

Key Components

Each agent consists of several basic components:

Core:

LLM: The brains—Sonnet 4.5, GPT-5.2, Gemini 3 Pro, or open source DeepSeek, Qwen, Llama. They process requests in natural language (or sound, video depending on modalities), form plans, pull tools, make decisions.

System prompts: Instructions about how the model should behave, determining its behavior, communication style and capabilities.

Tools: Instruments for interacting with the environment.

Additional: 4. Data sources: Same as tools, but specifically for passing data. 5. Auxiliary prompts: Ability to clarify how to do specific tasks without stuffing logic into the main prompt.

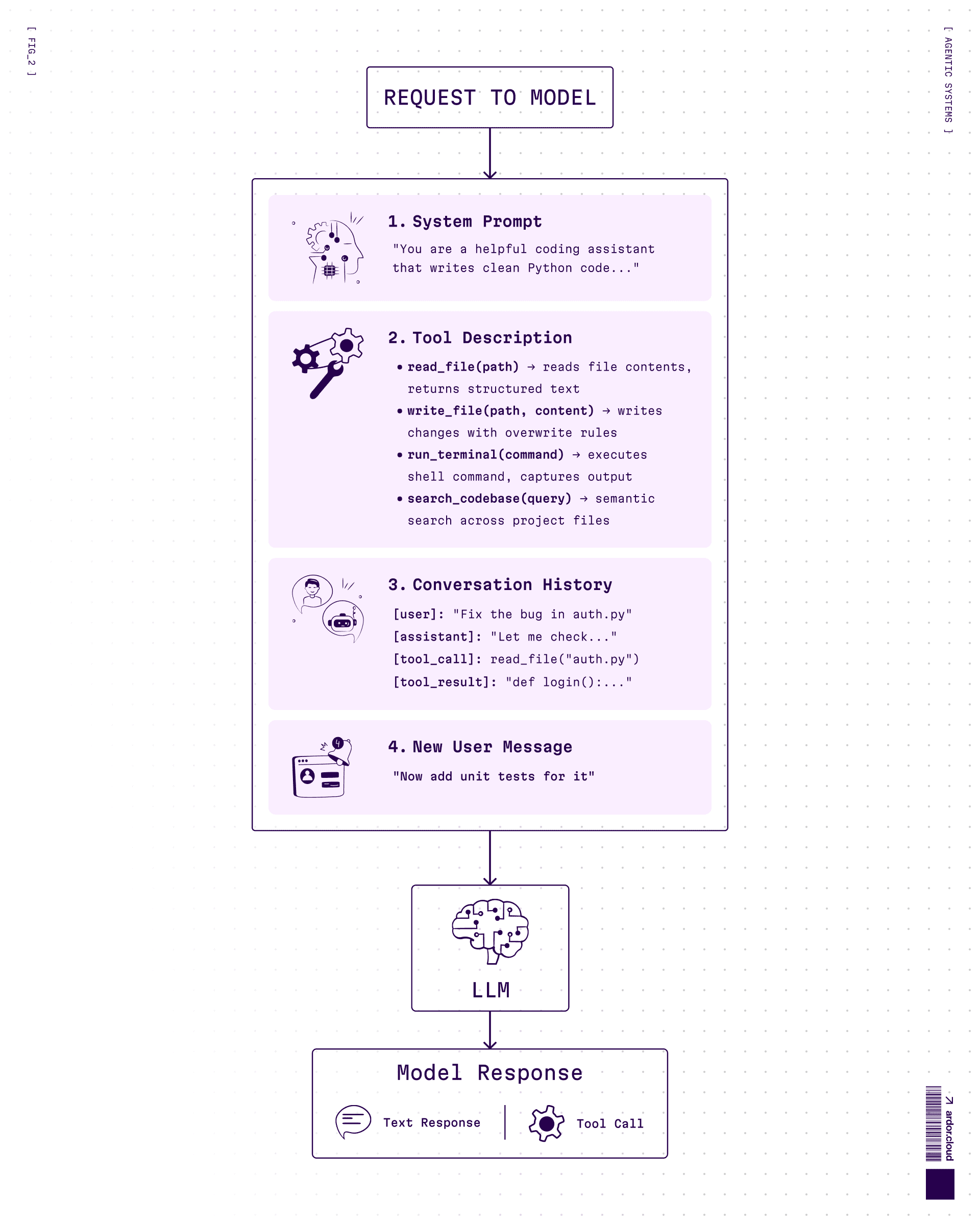

Here’s what a typical request to the model looks like:

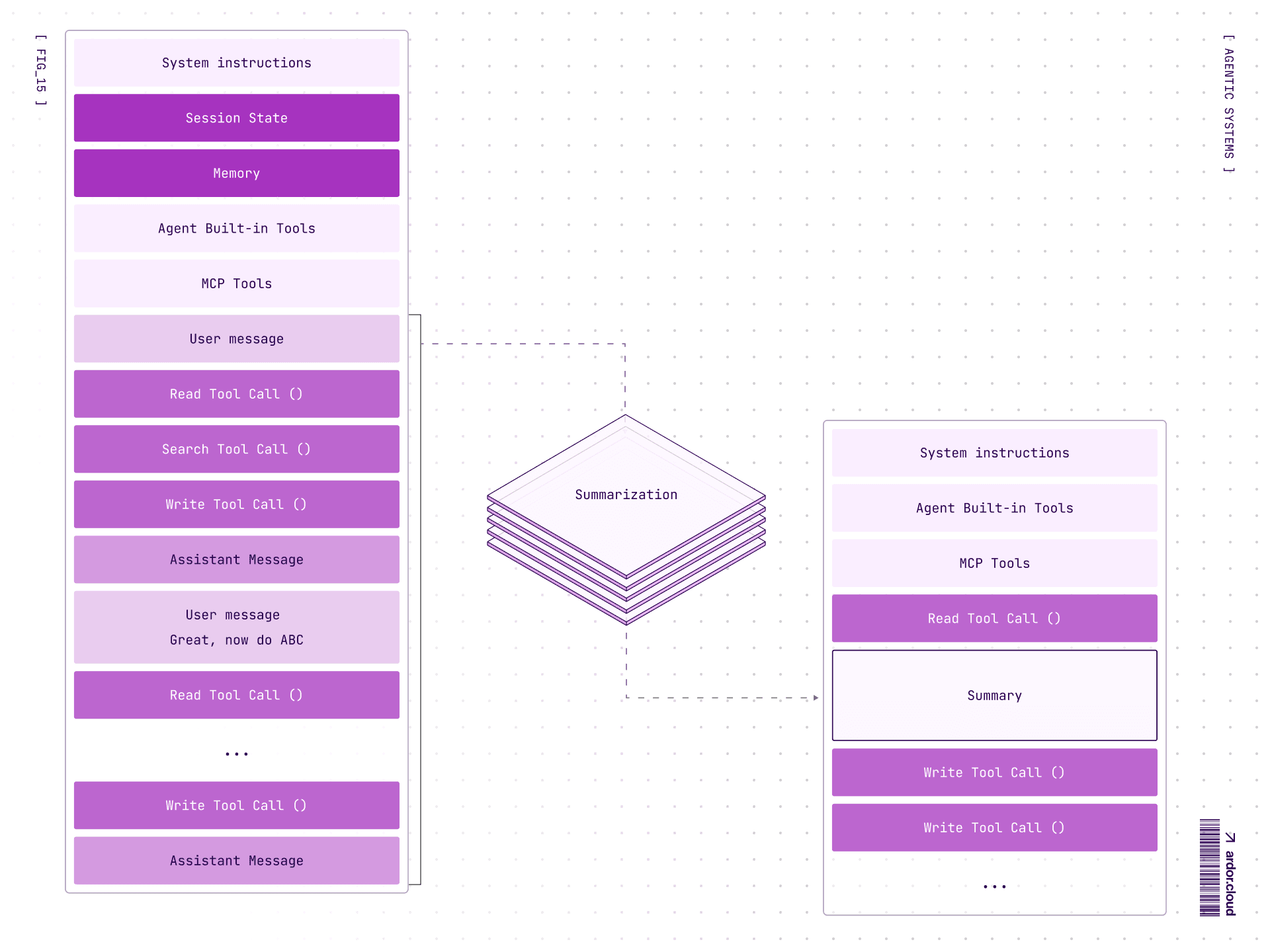

Everything above the new message is context. Yes, the bigger the context, the more tokens you pay for—but honestly, models are getting cheaper fast, so cost is not the biggest problem here.

The real problem? Larger context = worse attention to details. The model starts to “lose focus”, miss important information buried in the middle, hallucinate more. It’s not just about summarization—you need to actively control what goes into context.

Garbage in, garbage out.

If you stuff 100k tokens of irrelevant logs, don’t be surprised when the model ignores the one line that matters.

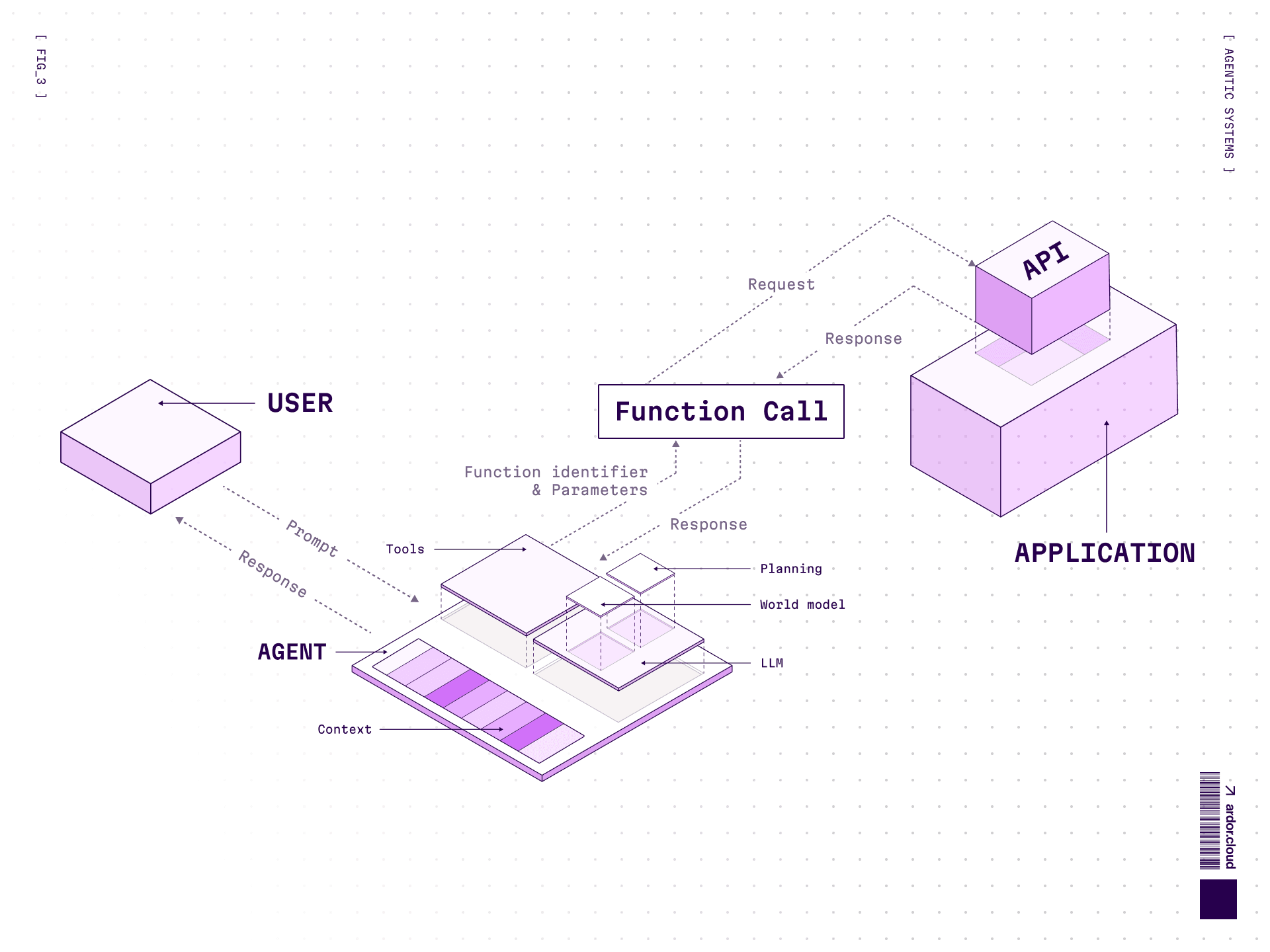

Function Calling

Before MCP everyone came up with their own way of handling model calls. In most cases the model produced structured output that a wrapper (the agent) intercepted, executed as program logic, and then returned to the model as a response.

In most cases, function calling is left to the model’s discretion—the model independently decides which tools to use. It selects the most appropriate tool from the provided list and returns a structured output containing the tool name and parameters.

Example: Imagine you need to deploy a service for data analytics.

You give the agent a task: “I need to analyze data from my application database”

Agent clarifies context through function calls—where you are in the system, which application you meant

Sees you’re in “My awesome App” in production environment

Decides to deploy Metabase for data analysis

Creates environment, configures application, adds Metabase, deploys to staging, checks logs and metrics, performs API checks to make sure everything works

All this is a chain of tool calls to influence environment state and gather feedback

Here’s how tools are defined and passed to the model:

The wrapper intercepts this, executes the actual API call, and returns the result to the model for next steps.

MCP (Model Context Protocol)

Currently the most widespread way to provide agent with tools, data and prompts is MCP.

MCP is an open protocol from Anthropic that explains how to wrap APIs, resources and more, so any agent can interact with them. Main value — you can separate agent (model, software wrapper) from available tools and resources, in theory 😏 And easily scaling them or connecting to third-party MCP servers.

MCP has following categorization:

Tools — functions that do something

Resources — access to files, data and more

Prompts — collections of prompts that can change agent behavior

Check MCP documentation here for more details.

By the way, behind a tool there can be another agent or assistant but it is more about internal tooling or A2A. Main feature: don’t make it interactive, so you don’t get a closed loop of message passing 😅

Designing Tools for Agents (ACI)

You know how much effort goes into UX design? Invest the same in Agent-Computer Interface. Your agent is like a very smart—but also very literally—a junior developer. If your tool description says ‘file path’ — expect it to pass ‘/path/to/file’ when you meant just ‘filename.txt’.

How to not shoot yourself in the foot:

Write tool descriptions like docstrings for someone who takes everything literally

Describe every parameter clearly — type, format, constraints. “date” means nothing, “date in YYYY-MM-DD format” means everything

Include examples: not ‘a file path’, but ‘e.g., /Users/john/documents/report.pdf’

Return clear, readable errors — not just 500. “User not found with email X” beats “Internal Server Error”. Agent won’t magically understand what went wrong.

Test how the model actually uses your tools. You’ll be surprised.

Poka-yoke everything: if a tool can be misused, it will be. Make wrong usage impossible.

From our experience: we spent way more time on tools, monitoring, tests and evals than on prompting the agent itself. Example: We need a patch tool for target file edits. Sounds simple — apply a unified diff to files. But when you want the model to generate diffs correctly? Oh boy. Good luck!

Through evals we iterated on validations, error messages, fuzzy matching strategies, edge case handling; until we got it to 99% stability. That’s dozens of test cases, monitoring dashboards, and a lot of “why the hell did the patch return conflict... oooohh whitespaces” debugging sessions.

And that’s just one example with one basic tool. Yes, an LLM can look like a genius—but really—it’s the fucking smart-ass genie from Aladdin 🧞♂️

And you NEED to learn how to control it.

Code Agents vs Tool-Calling Agents

Every tutorial/explanation about agents has an example with weather in three cities. We could too, but let’s be honest: When was the last time you needed to know the average temperature in Paris, Tokyo and New York simultaneously? Yeah, us neither.

So let’s look at a more realistic example. But first, what’s the difference?

Tool-Calling Agents (JSON-based)—generate structured JSON to call tools:

They work like a TV remote—you press buttons from a list. Reliable, predictable, but inflexible. The main problem is, they can’t store intermediate results between calls. Each call is a separate round-trip to the model, and that’s bad for several reasons:

Latency: each model call is ~1-3 seconds. 3 calls = 3-9 seconds of waiting vs one call.

Cost: with each call you pass the entire conversation history again. More tokens = more money.

Context bloat: the context grows with each step, model can “lose focus” on what matters

Hallucination risk multiplies: at each step the model can “forget” what it was doing or invent something new

Code Agents write and execute Python/JS code directly. Variables, loops, conditions—everything is available. One model call can generate an entire workflow. Plus they get immediate feedback from the environment—if something fails, the agent sees the error right away and can adapt.

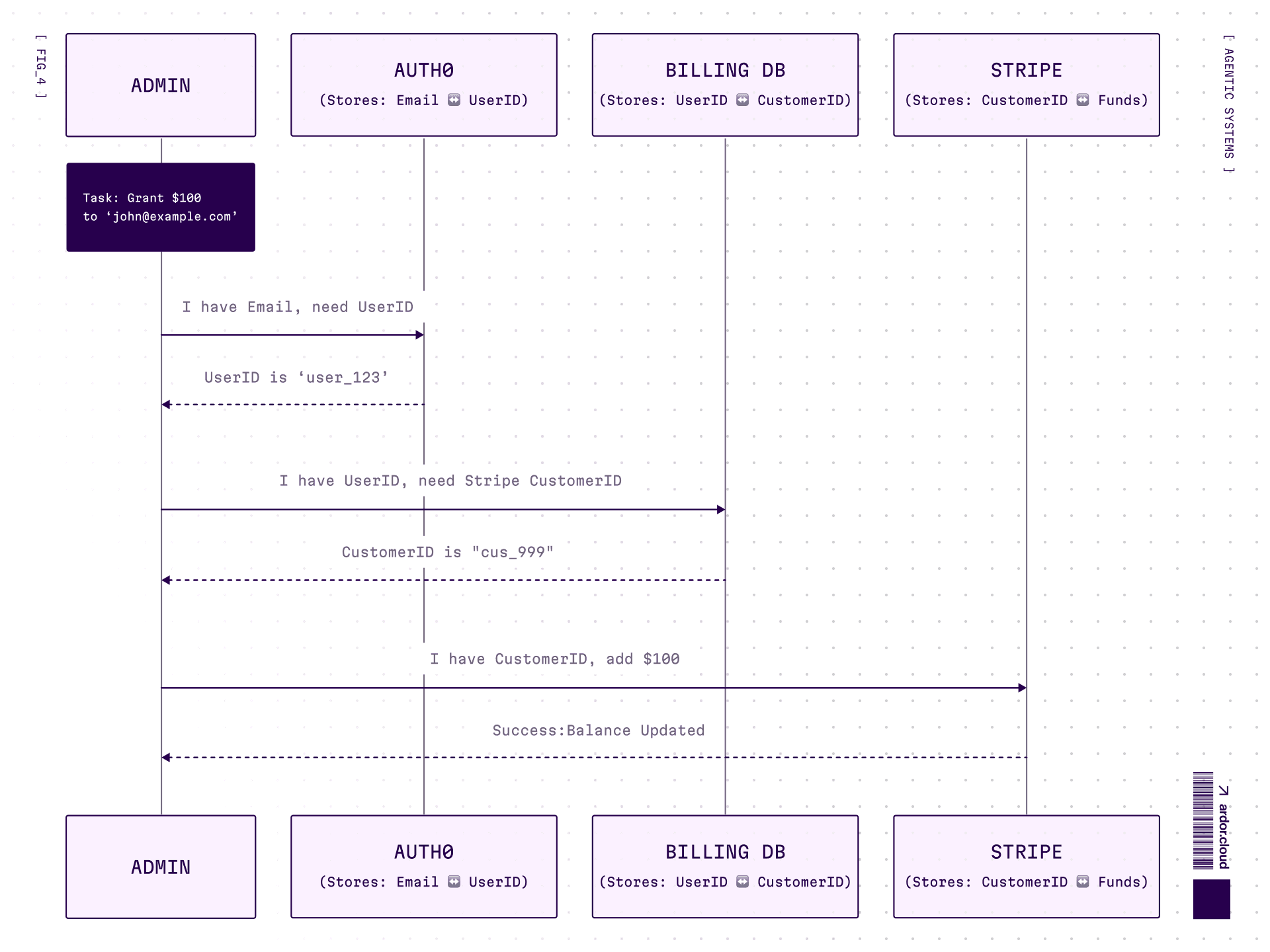

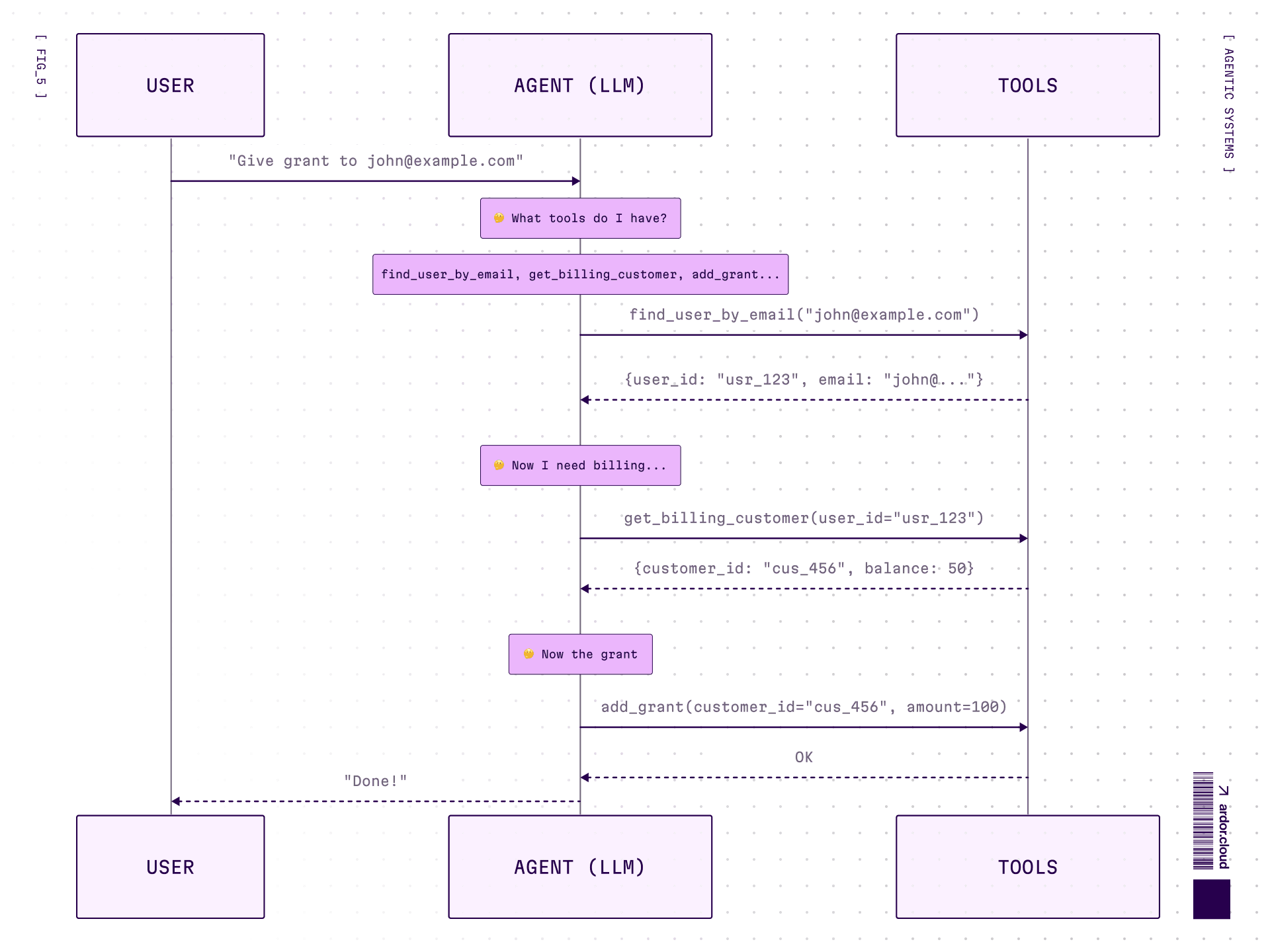

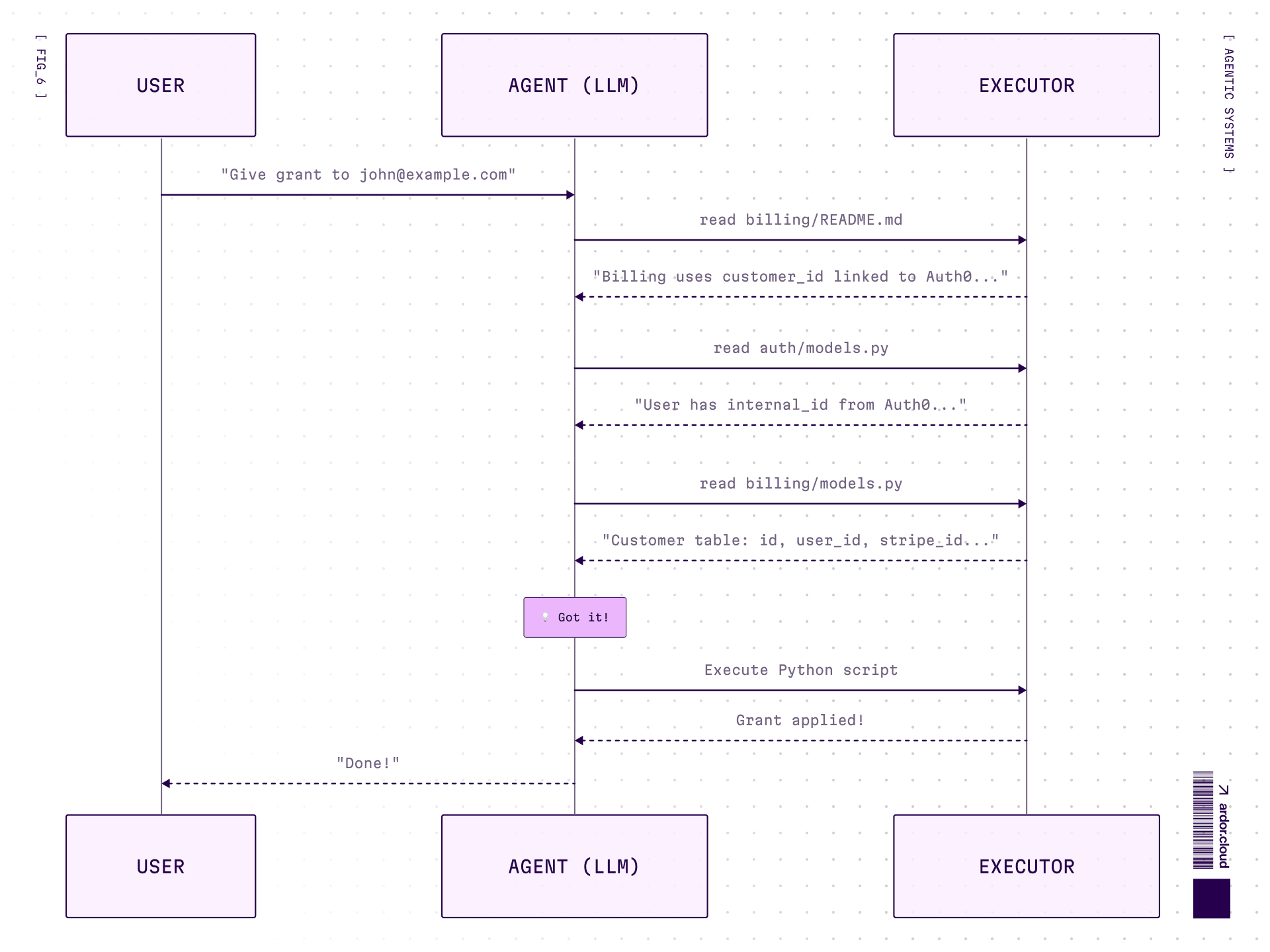

Practical Example: “Give a Grant to User”

**Task: “**Give $100 grant to user with email john@example.com”. That’s it! That's the whole request. Sounds simple, but here’s the catch — typical microservices architecture with separate databases:

The agent doesn’t know this structure. It needs to figure out how to connect email → user_id → billing customer → grant.

Tool-Calling approach:

Tools themselves are hints. Agent sees available tools and their parameters. That’s the discovery mechanism.

3 round-trips. Each time the model “thinks” again. Tool names and parameters guide discovery — if you designed them that way.

Here’s the catch: you’ll need tools for every operation. Either one tool per action (find_user_by_email, get_billing_by_user_id, add_grant) or bundle multiple functions into fewer tools. Either way — you end up with lots of tools, each requiring tests, evals, good descriptions, monitoring.

And the fundamental limitation: agent can’t solve a task if you didn’t give it the right tools upfront. No find_user_by_email? Stuck. Period.

Code Agent approach:

No predefined tools—agent needs documentation or has to explore the codebase itself.

Yes, the exploration is also iterative in this case. But here’s the key:

Tool-calling: every step is tool call → back to model → model thinks → next tool call. 3 actions = 3 round-trips.

Code agent: exploration is iterative, BUT execution is one script. Auth0 lookup + DB query + API call — all in one run, no model in the loop.

Plus:

Tool-calling needs pre-built, tested tools. No

find_user_by_email? Stuck.Code agent needs only file access. Figures out the structure, writes code that fits.

Trade-off: tools are more reliable (tested, clear contracts), code is more flexible (adapts to anything, but can break in creative ways).

Bonus: code agent can save the script with docs after solving a task. Next time similar request comes—search, find, reuse. Essentially building its own tool library on the fly. And these “tools” don’t bloat the context. The agent finds them via search only when needed.

Generated code (after exploration):

One execution. Not 3 round-trips. The agent figured out the structure and wrote the code that fits.

When to Use What

Tool-Calling | Code Agents |

|---|---|

Simple single-step tasks | Action chains with dependencies |

Maximum reliability needed | Flexibility and speed matter |

Weaker models | Strong models |

More details about code agents architecture, structured outputs and when they break will be covered in a separate article.

The Pyramid: From Simple to Complex

Now let's dive into each level of our taxonomy.

Remember: AI Function → Workflow → Assistant → Agent → Agentic System.

Pick the simplest level that solves your problem.

AI Functions

The simplest form. No planning, no complex behavior. One task, one call. Could be image classification, review classification, writing summaries, generating images in given style. No existential dialogues about meaning of life—just executing a specific task.

Architecture: Single LLM call with a focused prompt. Input → LLM → Output. That’s it.

Example: You make an application for personal budget management and need to teach it to work with any bank account statement exports. Banks have different formats. Writing code to support each one is complex—if the format changes, you’ll need to release an update.

Solution: Create a function with LLM under the hood, whose only task is to map data types from account statement file to your internal data structure. Now it adapts on the fly, even if the format changes.

No loops, no tools, no memory. Just one smart transformation.

Workflow Patterns

LLM follows a script you wrote. Input → Step 1 → Step 2 → Output. Predictable, debuggable, you control the path. Most production systems should start here. Graduate to agents only when the problem genuinely requires flexibility.

Here are the patterns from simple to complex:

Prompt Chaining — Assembly line for LLMs

Step 1 feeds into Step 2. Generate marketing copy → translate to {language you need} → check for cultural sensitivity. Each step is a separate call, easy to debug, easy to fix when something breaks.

When to use: Task can be cleanly decomposed into fixed subtasks. You’re trading latency for accuracy by making each LLM call easier.

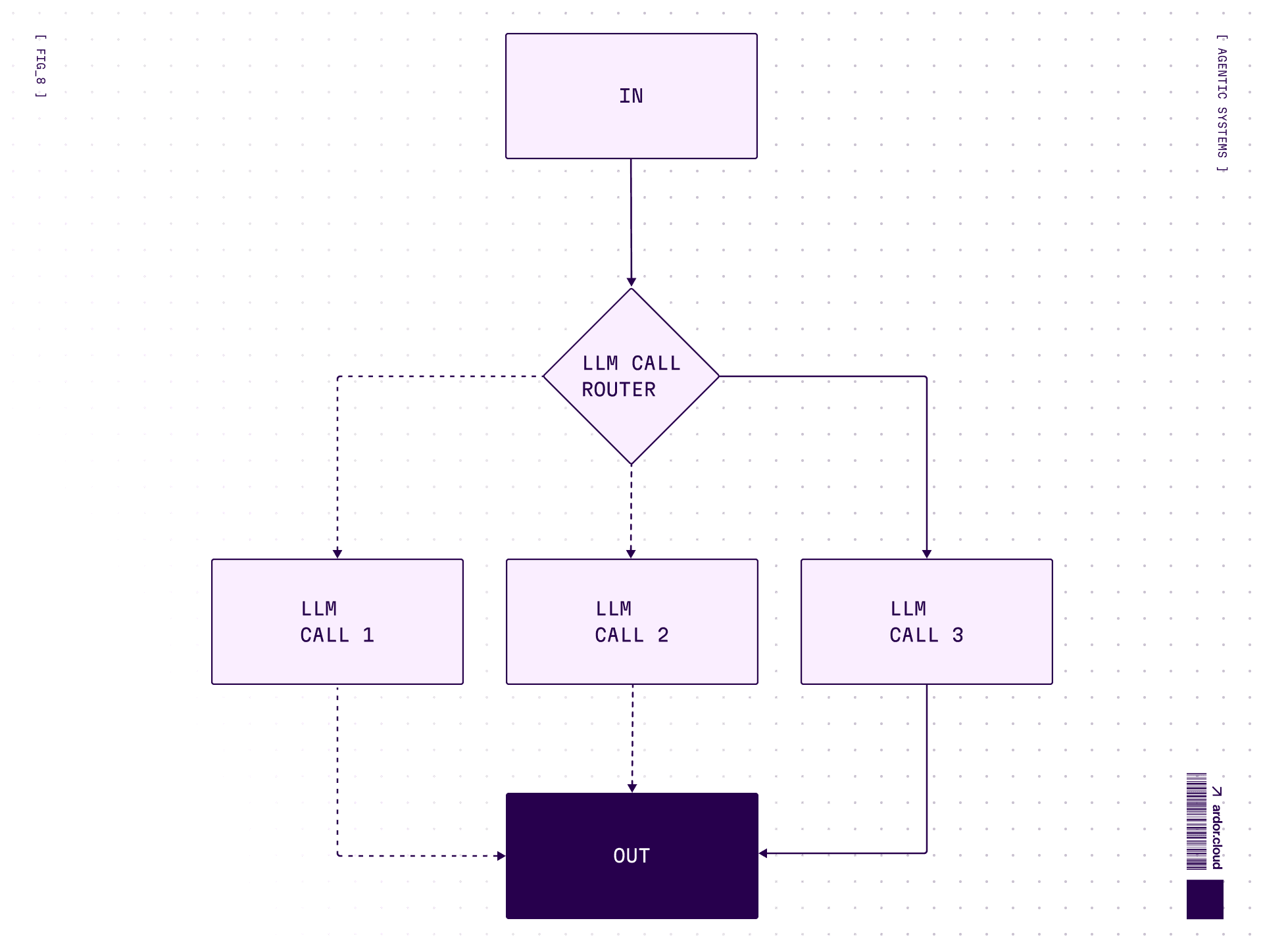

Routing — Traffic cop for requests

Classify input first, then send to a specialized handler. Support ticket comes in → is it billing? technical? complaint? → route to appropriate prompt/model. Cheap model for easy stuff, expensive for hard.

When to use: Complex tasks with distinct categories better handled separately. Classification can be done accurately.

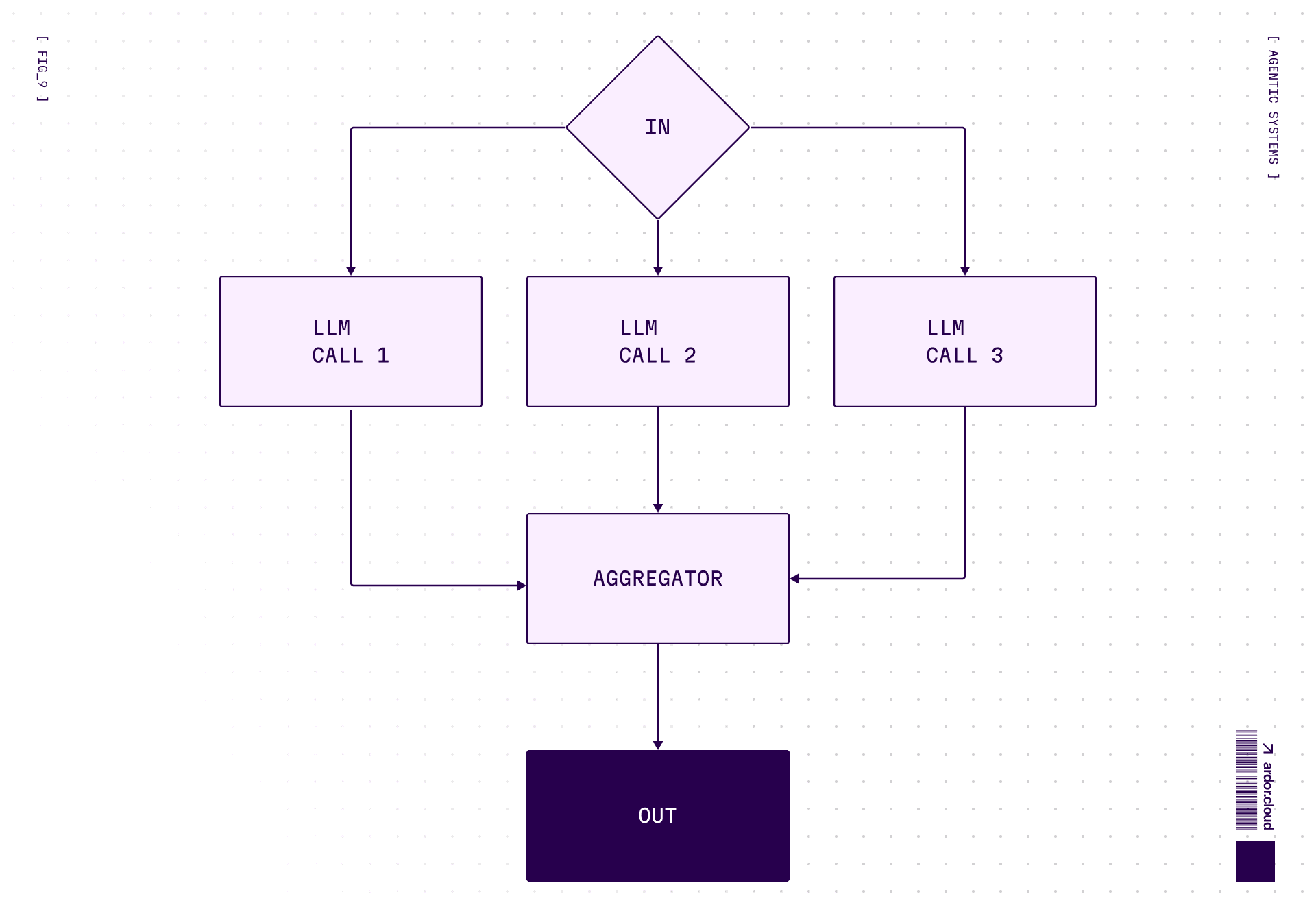

Parallelization — Divide and conquer

Same task, multiple angles. Two variations:

Sectioning: Break task into independent subtasks run in parallel

Voting: Run same task multiple times for diverse outputs

Code review? Run 3 prompts checking security, performance, style — simultaneously. Aggregate results. When you need confidence more than speed.

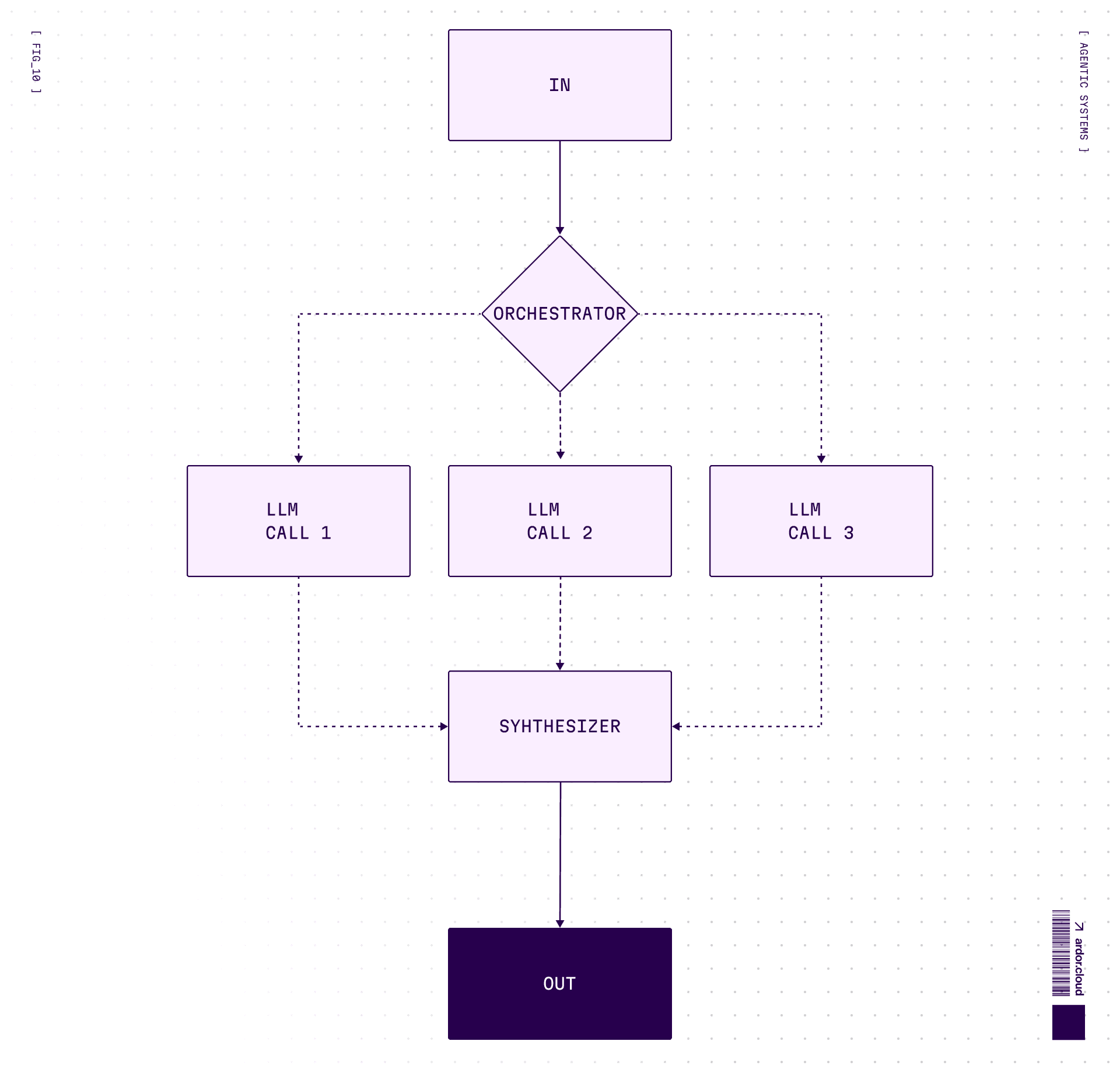

Orchestrator-Workers — Project manager mode

Central LLM dynamically breaks down tasks, delegates to worker LLMs, synthesizes results. Key difference from parallelization: subtasks aren’t pre-defined, but are determined by orchestrator based on input.

Think of a coding agent editing multiple files — one brain decides what needs to change, workers execute the actual edits.

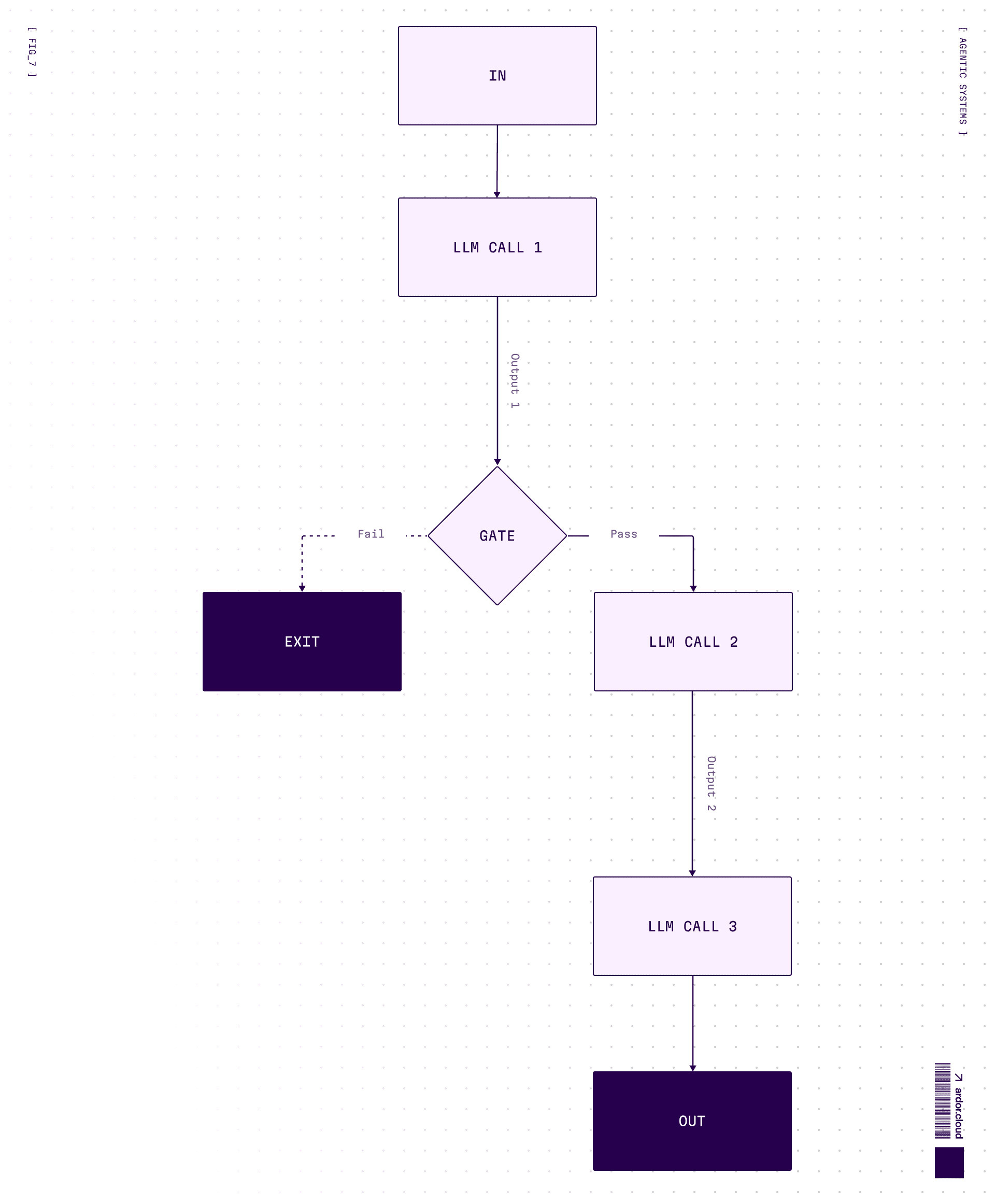

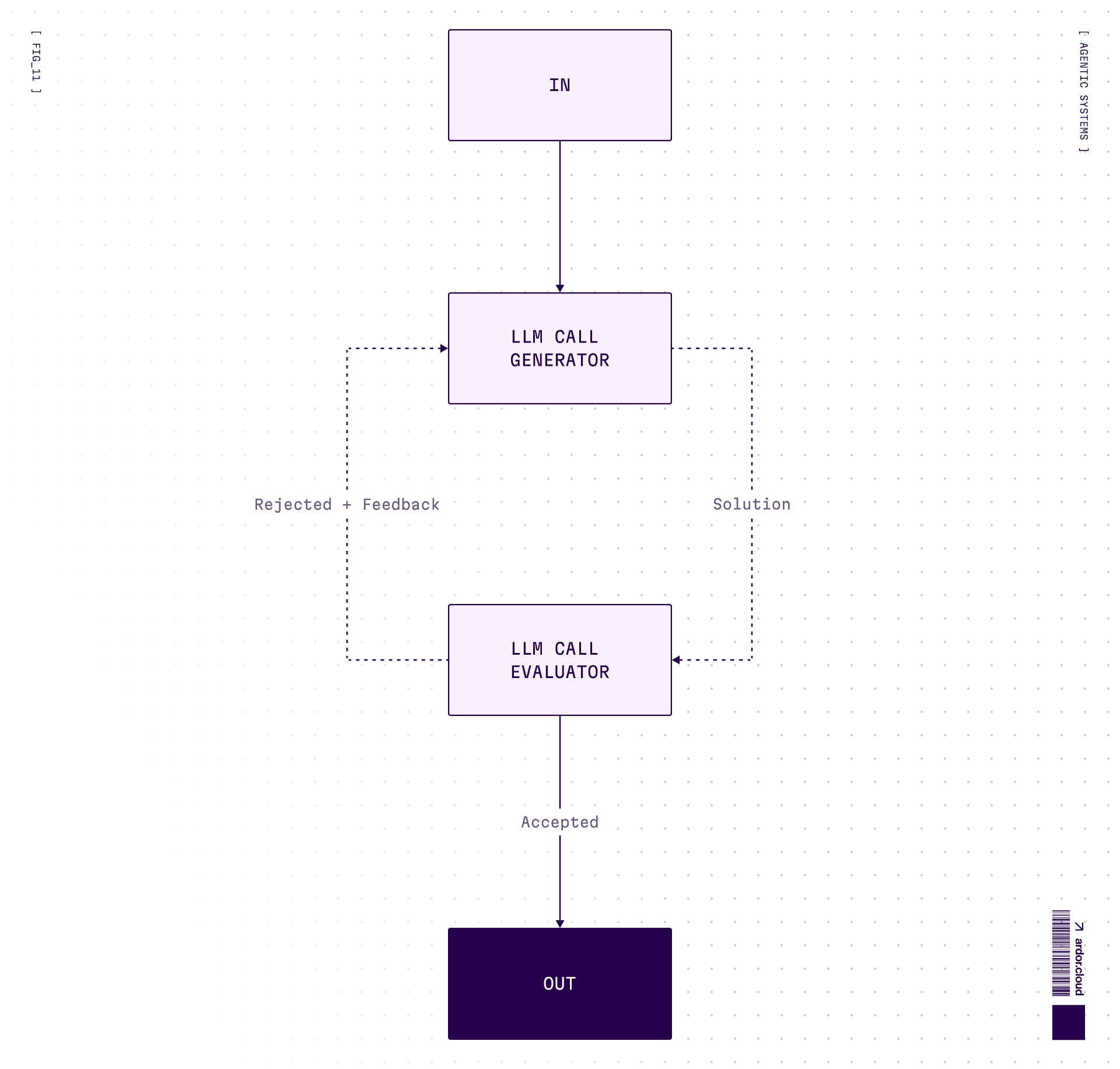

Evaluator-Optimizer — The Perfectionist loop

Generate → evaluate → feedback → regenerate. One LLM generates, another evaluates in a loop.

Good for creative tasks where “good enough” isn’t. Translation, writing, code that needs to pass tests. Warning: can loop forever if criteria too strict. Always set max iterations.

Assistants

Can maintain dialogue on various topics, do quick search through sources. Usually can’t change environment state or influence external world.

Examples: ChatGPT, Claude, Grok—chat interfaces with minimal capabilities to actually do something.

Main task: Maintain dialogue and give consultations. Can make plans, but usually limited in capabilities to execute them.

Architecture: LLM + conversation history + maybe some read-only tools (search, retrieval).

The key difference from agents: Assistant does something only with human participation. It’s reactive—you ask, it answers. Like a support chatbot that can consult and provide information, but can’t actually do anything itself.

Or a study assistant—can explain complex topics with simple examples, generate learning plan, give code examples. But write and test a program itself? Can’t.

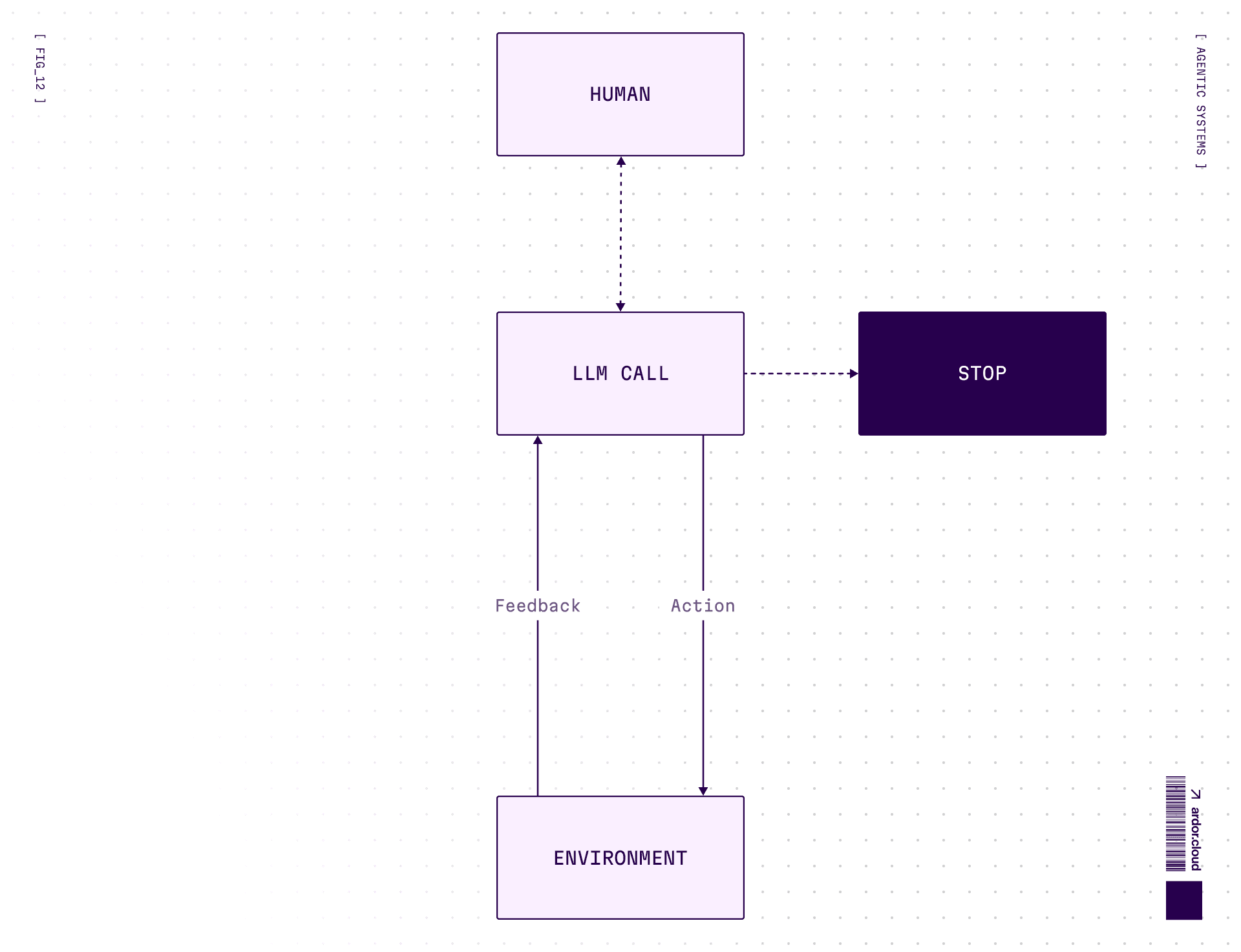

Agents

This is where things get interesting. Advanced assistants with:

Complex memory configuration

Large set of tools

Ability to influence environment state (change settings, write code, call APIs)

Can plan and execute actions according to plan

Complex behavior based on environment state and its changes

The key difference: Agent can perform actions independently and make decisions based on feedback from the environment.

Request data → do something → check how environment state changed → decide what to do next.

Architecture: LLM + tools + memory + feedback loop. The agent decides which tools to use and when.

When to use: Open-ended problems where you can’t predict required steps. You can’t hardcode a fixed path. You have some level of trust in model’s decision-making.

Warning: Agents mean higher costs and potential for compounding errors. Test extensively in sandboxed environments.

Agentic Systems

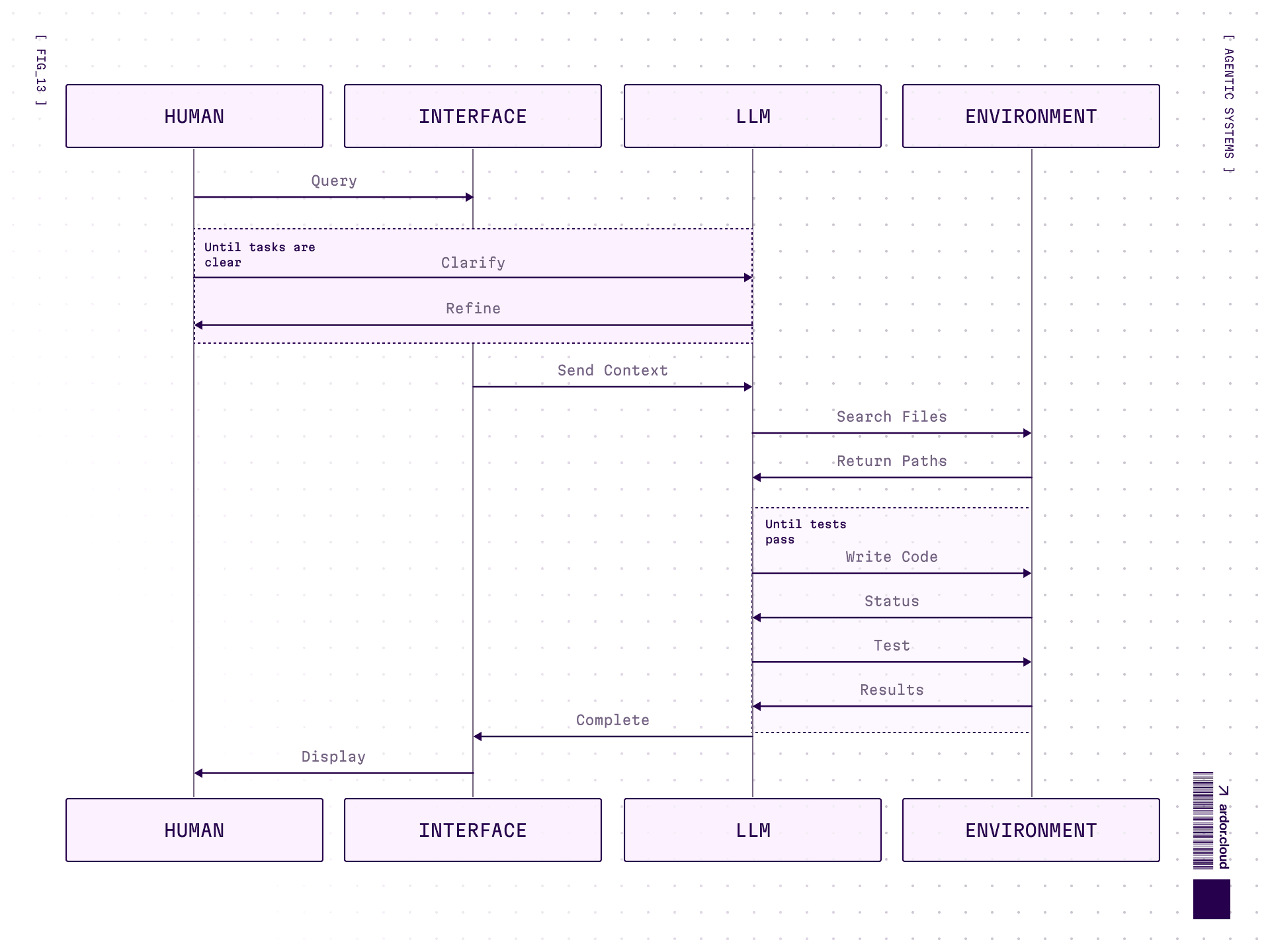

Specialized agents with UI and tools for solving specific tasks. If simple AI-agent can be general purpose—then the agentic system is sharpened for specific tasks with appropriate tools and UI.

Examples: Ardor, Cursor, Lovable, Claude Code. They have:

Clear task domain

Specialized tooling

UI for user control and oversight

Architecture: Agent + specialized tools + UI + domain-specific prompts.

Example: Ardor can receive signal from monitoring system about a problem in deployed application. Independently check logs and metrics, conduct code analysis to find problem, make patch, deploy to test environment, check functionality—and when user comes, they’ll only need to validate the result.

Multi-agent variant: Agentic systems can be one agent with many tools, OR multiple specialized agents working together. Why multi-agent? Specialization and division of labor. If you stuff everything into one agent—its prompt becomes dimensionless and its quality suffers.

Fair warning: multi-agent systems are currently complex and fragile. Resort to them only when you’ve exhausted single-agent possibilities. Main challenge—control and debug complexity.

Agent Interaction with Environment

An averaged example of agent interaction with environment:

Perception: Collecting data about what’s happening in the environment

Reasoning: Analysis and decision making to think through actions

Action: Actions to change environment state

And then again. For an agent it’s critically important to have access to environment feedback directly, to interactively check what works and what doesn’t.

Inside the reasoning-action part there can also be memory (usually short-term) and learning (within session or with external storage) — cursor rules or ardor.md/claude.md are examples of such in context memory-learning. Models can’t yet learn on the fly, changing their weights to remember something new. But they can write in a notebook, so it can be reused in the future.

One technique for managing long sessions is Intentional Compaction — instead of passing the entire conversation history (which bloats context and costs), the agent periodically could summarizes progress to a file or record in database and references it in future calls. This keeps context focused and costs down.

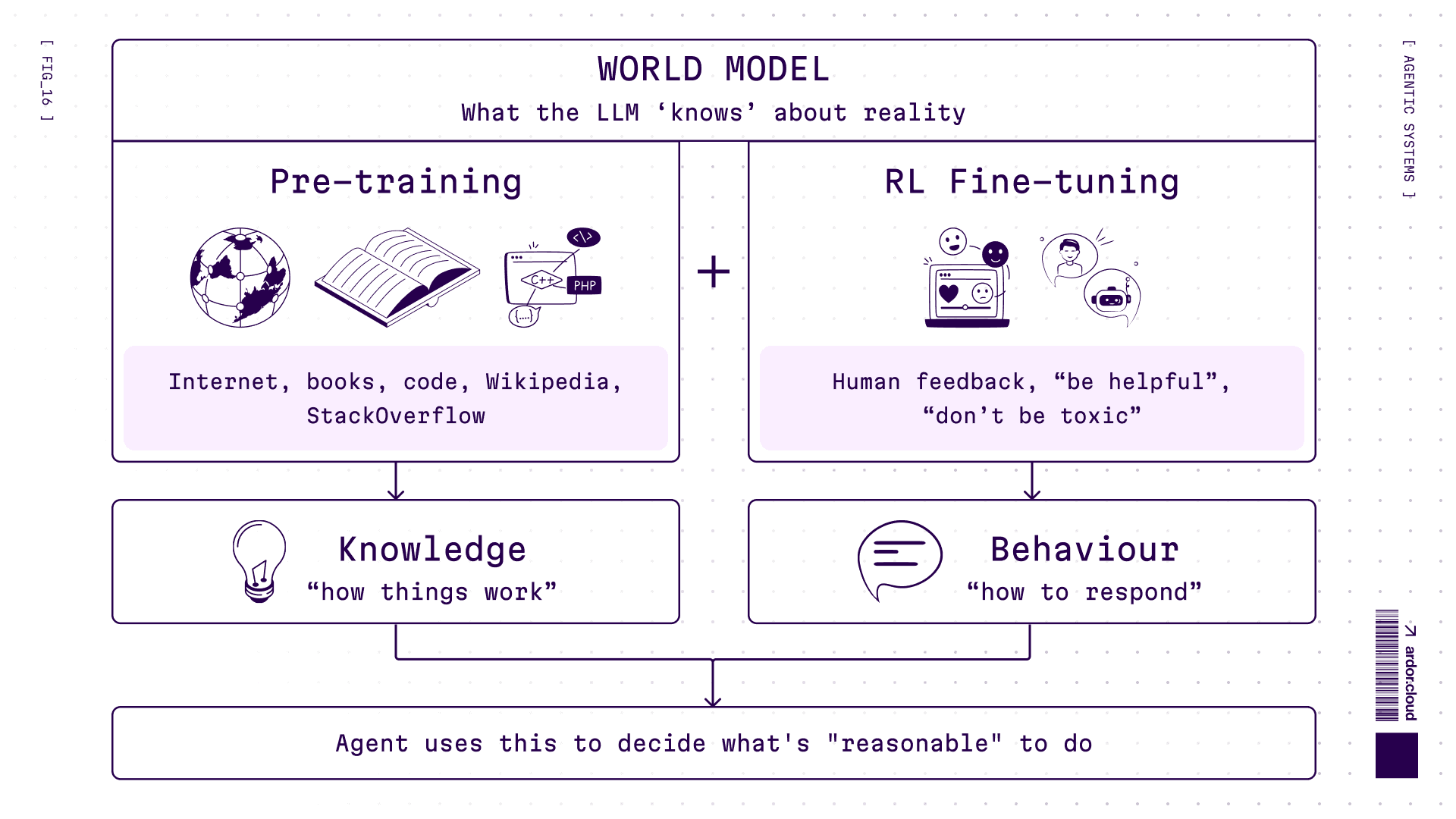

Agent behavior is influenced by incoming information about environment state, its system prompt, and world model inside the LLM.

About World Model

“World model” is what the LLM “knows” about how things work—physics, coding patterns, social norms, whatever. It comes from two sources:

Pre-training: terabytes of internet text. Model learns patterns: “after

defcomes function name”, “water freezes at 0°C”, “users get angry when you ignore their questions”RL fine-tuning: reinforcement learning shapes how model responds. Be helpful, don’t be toxic, follow instructions, admit uncertainty. Trial and error with human feedback.

Why this matters: world model determines what agent considers “reasonable”. Never saw Kubernetes configs during training? Will hallucinate YAML. RL taught it to be overly cautious? Will refuse risky but necessary actions.

And yes, welcome to the holy war: is this “real” understanding or just pattern matching? I know, I know — Yann LeCun (godfather of deep learning) argues LLMs don’t have true world models at all. He’s building JEPA (Slavs, stop giggling)—Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture learning causal relationships instead of predicting tokens. Might be the next revolution. Want details? Hit us up—we'll do a deep dive.

What Can They Do — Use Cases

1. Customer support: Not just links to documentation. Actually understand a user’s problem and give actionable answers. “Your problem can be solved like this” instead of “here's a link, good luck”.

2. Marketing: Market research, competitor analysis, data extraction from reports. What took weeks, can now one request.

3. Sales: Analyze client behavior, generate personalized offers, automate campaigns and content production.

4. Analytics: Query SQL databases, run Python analysis, identify patterns and anomalies. Speed up product teams by orders of magnitude.

5. Business operations: Automate what was economically unfeasible. Invoice processing where half the fields are empty and you need context of counterparty and SKU codes. LLM with database access handles it.

6. Science & Research: Design experiments, analyze results, validate hypotheses. With robotic lab equipment or simulations, agents can actually run experiments, not just plan them. From “what if we tried X?” to autonomous hypothesis testing loops.

7. Software development: Write code, generate apps from prompts, debug issues, refactor legacy code. Cursor, GitHub Copilot, Windsurf—agents that read your codebase, understand context, and write code that fits.

8. DevOps & Infrastructure: Deploy services, manage configs, debug production issues. Best practices exist, documentation exists—agent reads and executes. Same stuff a DevOps engineer would do, but at 3am without complaining. 😂

And here’s the punchline: everything is code!

Code is the most powerful tool for interacting with the real and virtual world. We’ve been developing it since Computer Science became a thing (~1950s). And if you go even deeper, it’s all text. The current AI revolution is built on good old writing, just electronic now. Petabytes of Reddit memes, StackOverflow chaos, scientific papers, pulp fiction, Wikipedia rabbit holes—that’s the foundation. Agents already have the ultimate interface.

Wait, Do You Actually Need an Agent?

Before we dive into implementation, here’s a sobering reality check. Not everything needs an agent. Sometimes a well-crafted prompt to a single LLM call is enough. Adding agents is like adding microservices: sounds cool, but now you have distributed systems problems.

Here’s a simple test:

Can you flowchart it without crying? → Just write code. Seriously. If-else, switch-case, done.

Would you trust a junior with documentation to handle it? → Agent territory. There are best practices to follow, but inputs are fuzzy, context matters, and you can’t predict every edge case upfront.

Is latency critical? Can’t afford “creative interpretations”? → Maybe stick with deterministic code. Agents think, and thinking takes time. And sometimes they get... creative.

Now, I can’t stop you from putting an agent in a rocket guidance system or running an operating room. And honestly? I’d love to watch. But you’ve been warned. It’ll be an adventure, and you’ll collect a lot of bruises along the way 🚀🏥

How to Implement

Worth considering: models train on publicly available data, so better give them widely known tools if you plan to give model ability to use them.

Understand technology limitations: What it can solve and what it can’t. Simplest variant: if you have a person in team who already solves this problem and can explain in words how to solve it—then it most likely can be solved by an agent too.

Identify problem spots: How to form prompt for agent that would explain how to solve this problem. Best is to distill expert knowledge. Collect few dozens examples and test system on them. Same expert evaluates results.

Define success metrics: What will be considered successful implementation and what failure? Reduced first line load by 50%? Hooray! Celebrate. Didn’t work out? Figure out why and determine if this can be solved.

Think about evaluation: If it’s a chat agent, definitely think how quality of responses will be evaluated. Usually like/dislike on message is already good data source. If you also add form for collecting why good/bad—even better. Provided someone will process this data and make changes.

Launch pilot: At minimal scale to test main system operation. If everything’s ok, scale and carefully monitor metrics and user feedback.

Evals Are Not Optional

This is the one everyone skips and regrets. You can’t improve what you don’t measure. Set up evaluations from day one:

User feedback: thumbs up/down is already gold

Success metrics: what does “working” even mean for your case?

Regression tests: did the new prompt break old cases?

Without evals you’re not engineering—you’re vibing. And vibing doesn’t scale.

Risks to Consider

Two main ones:

Model hallucinations: makes up what doesn’t exist.

Sensitive data: sending them to model provider. Can solve either by running local LLMs for full control or signing Enterprise agreements with providers where they swear they won’t use your data for training. And if you’re really very sensitive, start designing your own hardware to be sure there are no backdoors 😁

Security considerations:

The agent can’t be an access authenticator because it can always be tricked with stories about grandma who told you company secrets as a fairytale before sleep. All authentications and authorizations should be programmatic. Agents shouldn’t have more rights than users working with it.

Check out Guardrails for ensuring secure model operation and OWASP Top 10 for LLMs for updated list of security threats.

Real World Examples

SWE Agents

Ardor, Cursor, Claude Code, Warp help with code writing and debug. They can dig around in logs and infra, and they usually work in several steps:

Look at the current state

Plan how they’ll change state

Write code

Test (well not all can do this, often the user is present at this step)

Repeat

Assistants

ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, Grok—same LLMs under the hood, but often limited by the question-answer cycle. Mainly advanced search engines. Give answer, check grammar, draw picture in Ghibli style. Some can already book tickets or create calendar events.

Assistants are now quite widespread as the first line of support—almost every SaaS has a chatbot on their website where lambda with access to documentation answers you first.

Business Cases

More interesting cases: agents in supply chains that automate specific tasks like document verification and requesting needed ones if something’s missing. Or with database access for creating forecasts based on data.

What’s Next, What to Expect?

Once AI went through its winter—there wasn’t enough computing power and data for things like LLMs.

Today—easily accessible data from the internet is already exhausted. Corporations have closed datasets that could give more useful training data, but getting access is extremely difficult. Besides, the real world and the textual world are very different 😁

AI and agentic systems development will increasingly go by observe-think-do-observe pattern, creating new data from real world feedback.

AI now is mainly an assistant that can automate the routine, but still needs humans to set the right vector. Think of it as a junior on max level—capable of quickly doing something, making mistakes, fixing, and through quick iterations getting to result. Therefore the basis of AI implementation currently is clear understanding of its limitations and clear task setting.

Yes, creating and implementing AI today is still part art—the model is a probabilistic generator. But approaches are rapidly developing and current costs are investments in competitive advantage.

One more thing: the current wave is powered by two core architectures—transformers and diffusion models. Both work across modalities now: transformers generate images (DALL-E 3, Sora), diffusion generates text (Google’s experiments). But research into new architectures is active. We mentioned JEPA earlier, there’s also state space models (Mamba), mixture of experts, Google’s Titan (with neural memory that actually learns during inference, my favorite one), and approaches we haven’t seen yet. These won’t be the only architectures forever. Stay curious.

TL;DR: Four Principles for Agents That Don’t Suck

After all this, what actually matters?

1. Start stupid simple

Don’t build multi-agent orchestration when a prompt template would do. Add complexity only when you’ve measured it helps. Keyword: measured.

2. Make thinking visible

If your agent is a black box, debugging it is a nightmare. Log everything. Show planning steps. When it fails (and it will), you need to know why. Especially how it uses tools, success rate, what are systematic issues.

3. Treat tool design like UX design

Your agent will use tools exactly as described, not as intended. Write descriptions for a smart but literal reader. Test extensively. Make wrong usage impossible.

4. Evals are not optional

This is the one everyone skips and regrets. You can’t improve what you don’t measure. Set up evaluations from day one:

User feedback (thumbs up/down is already gold)

Success metrics (what does “working” even mean for your case?)

Regression tests (did the new prompt break old cases?)

Without evals you’re not engineering, you're vibing. And vibing doesn’t scale.

And yes, Ardor helped write this article—proofreading, style fixes, the boring stuff. That’s what agents are for: handling the tedious so you can focus on what matters. 🤖