Agentic Systems

AI Agents

Skills

Skills: The Architecture Shift Behind Shippable AI Agents

As AI agents moved from demos into real production environments, a limitation became hard to ignore. Having access to models and tools wasn’t enough—capability needed to be deliberately built into the system.

Introduction: Agents Worked—Until We Tried to Ship Them

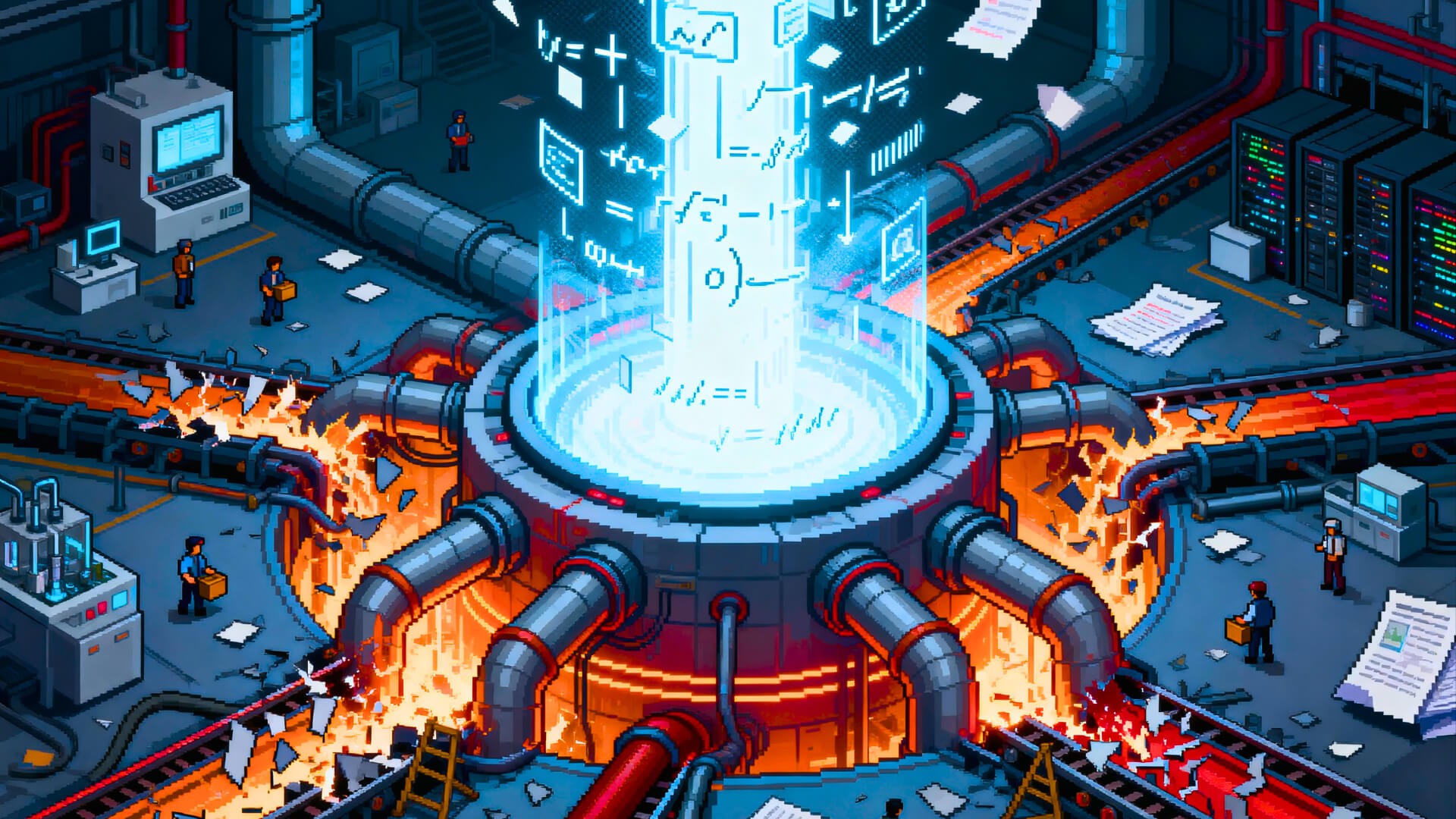

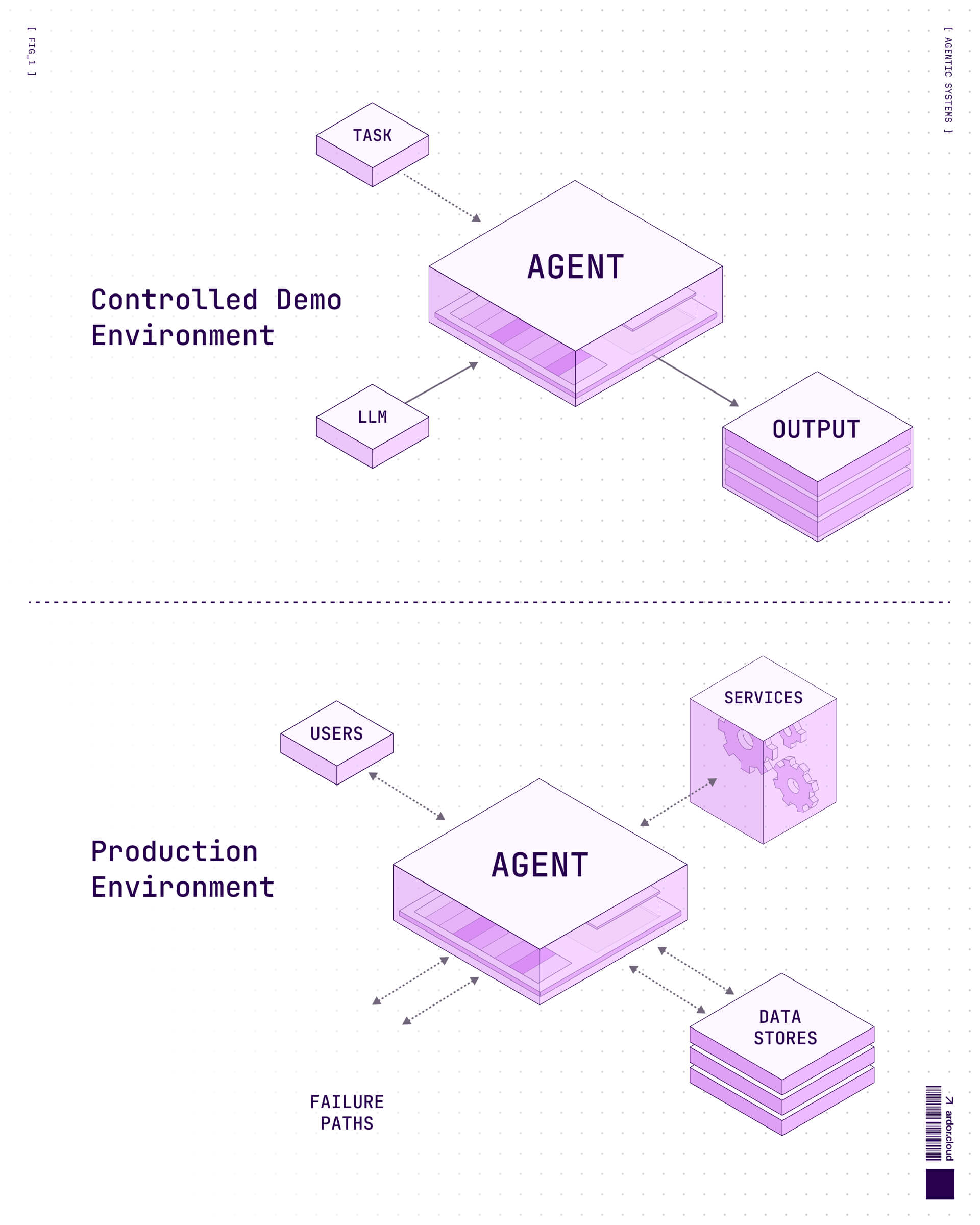

Every AI engineering team has experienced this moment: the agent demo that works flawlessly in the all-hands, then implodes spectacularly in production. The pattern is so consistent it's almost algorithmic. Single-agent loops—those beautiful prompt → model → output cycles that look like magic in controlled environments—encounter users, services, data stores, and failure paths, and suddenly the magic disappears.

This isn't a model problem. GPT-4, Claude, Gemini—they're all capable enough. The issue is architectural. We've been trying to solve production problems with demo-grade patterns, and the gap between those two realities is where most agentic systems currently die.

The evolution from monolithic prompts to MCP (Model Context Protocol) to skills represents something more significant than iterative improvement. It's the difference between agents that perform parlor tricks and agents that ship software. Understanding this progression isn't just intellectually interesting—it's the difference between agentic systems that work in slides and agentic systems that work in production.

Before Agents: Monolithic Prompts

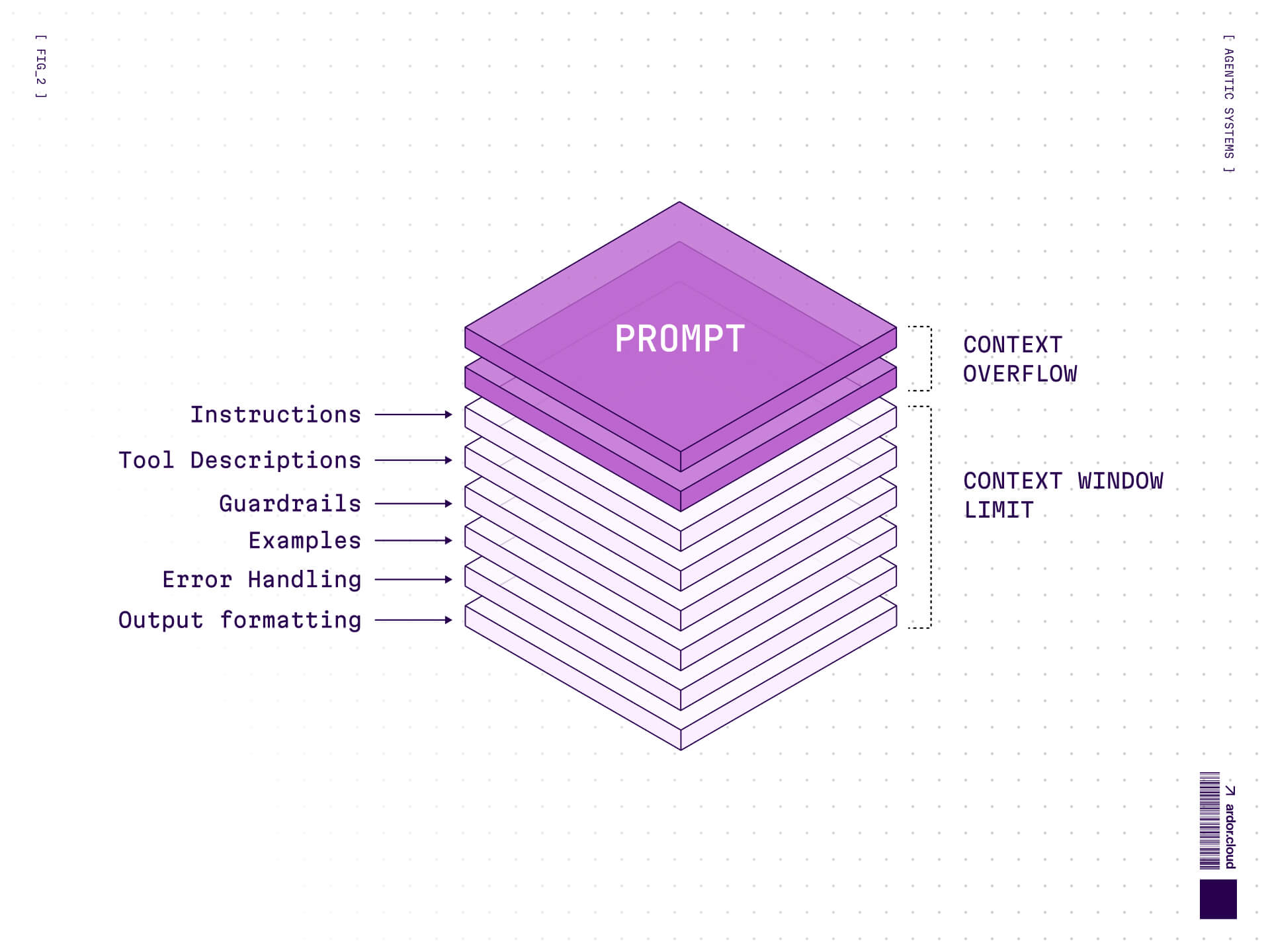

The first generation of "agentic" systems weren't really agentic at all. They were monolithic prompts masquerading as intelligence. You'd have a single, massive instruction block containing:

Task instructions

Tool descriptions

Guardrails and constraints

Context and examples

Error handling logic

Output formatting requirements

This approach had a seductive simplicity: everything the model needed was right there in one place. But that simplicity was brittle. Every new requirement inflated the prompt. Every edge case added another paragraph. Every tool meant more tokens spent on descriptions the model might never use.

The context window became a garbage dump. Models would lose critical instructions buried in the middle. Token budgets evaporated before reasoning even began. And worst of all, these prompts were impossible to version, test, or debug systematically. You couldn't A/B test instruction phrasing without risking downstream breakage. You couldn't isolate what was actually influencing model behavior.

Prompt engineering at scale faces fundamental limitations around instruction density and context management. The monolithic approach simply doesn't scale beyond toy examples.

Monolithic prompts worked for demos. They failed for products.

Phase One: MCP and Orchestration

Why MCP Emerged

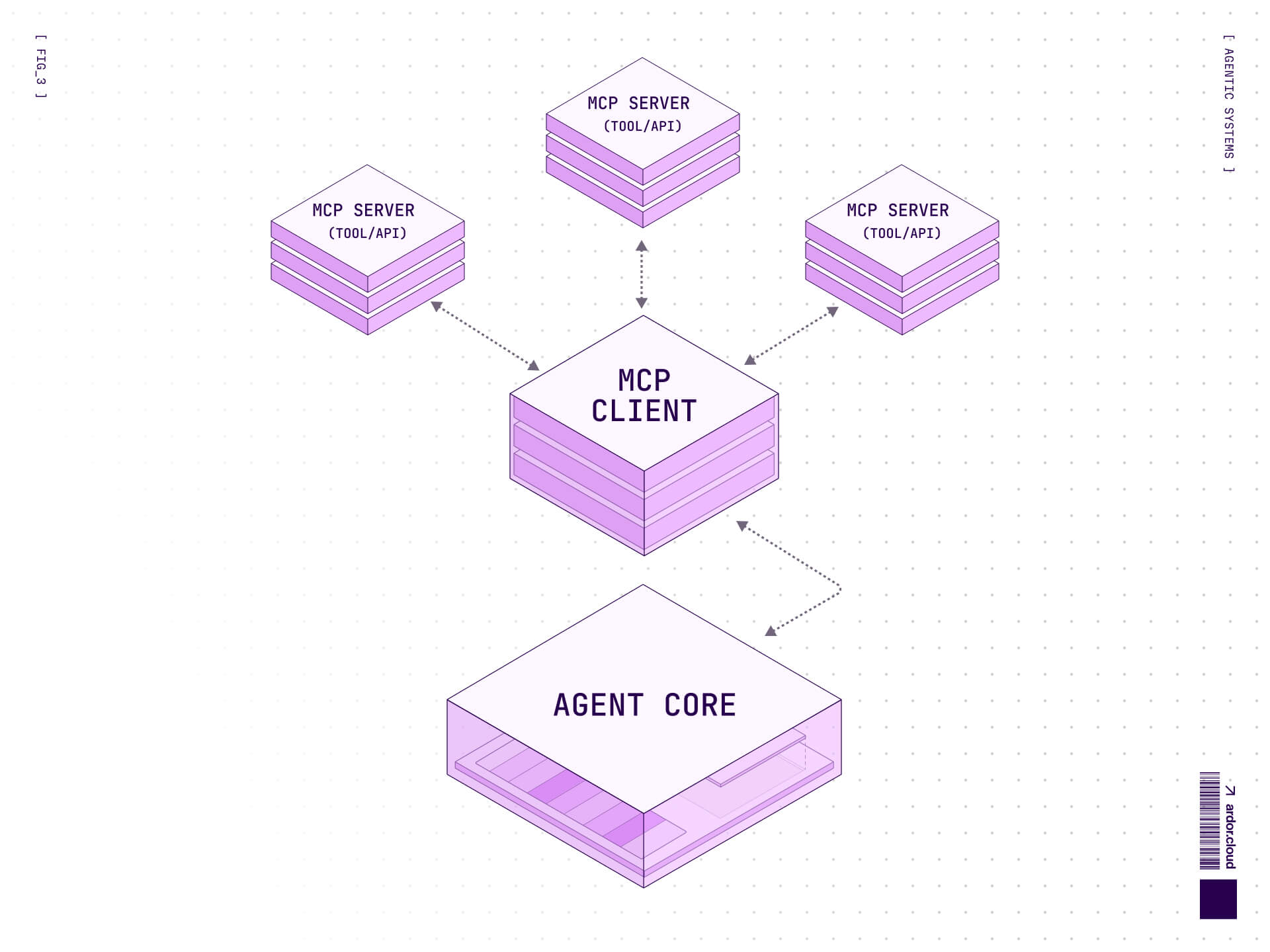

MCP emerged as an answer to a real problem: agents needed structured ways to interact with external systems. The Model Context Protocol, introduced by Anthropic in November 2024, provided exactly that—a standardized interface for tools, data sources, and services.

The architecture was clean: separate the orchestration (planner → executor → tool → verifier) from the execution. Let agents coordinate through message passing. Define clear boundaries between reasoning and action. MCP gave us the vocabulary to build multi-agent systems that could actually compose.

MCP as a Standard

MCP's real contribution wasn't technical sophistication—it was standardization. Before MCP, every agent framework had its own tool-calling format, its own connection protocol, its own serialization format. MCP created a common language.

Think of it as infrastructure. Just like HTTP didn't enable networked computing (you could always write custom protocols), it made networked computing scalable. MCP does the same for agent-to-tool communication. It's a hub-and-spoke protocol where the agent sits at the center and external systems become standardized ports.

This matters enormously for ecosystem development. When tools speak MCP, they work with any MCP-compatible agent. When agents speak MCP, they can connect to any MCP-compatible service. The combinatorial complexity collapses.

Where MCP Hit Its Limits

But MCP exposed a new bottleneck: the context window itself.

Here's what actually happens when you use MCP at scale. Each tool requires a schema definition. Each server connection adds protocol metadata. Each capability needs documentation. All of this goes into the context window before the agent can even begin reasoning about the actual task.

Token limits remain finite, even as they expand. A GPT-4 context window might seem generous at 128K tokens, but watch what happens when you integrate a dozen MCP servers, each exposing multiple tools, each tool carrying detailed schemas and examples. Suddenly you're spending 30-40K tokens on infrastructure before the agent writes a single line of code.

The reasoning space collapses. The agent becomes a thin orchestration layer frantically juggling protocols instead of solving problems. This is MCP's most important failure mode, and it's not theoretical—it's the lived experience of every team that tried to ship MCP-heavy agents to production.

MCP solved connectivity. It didn't solve capability.

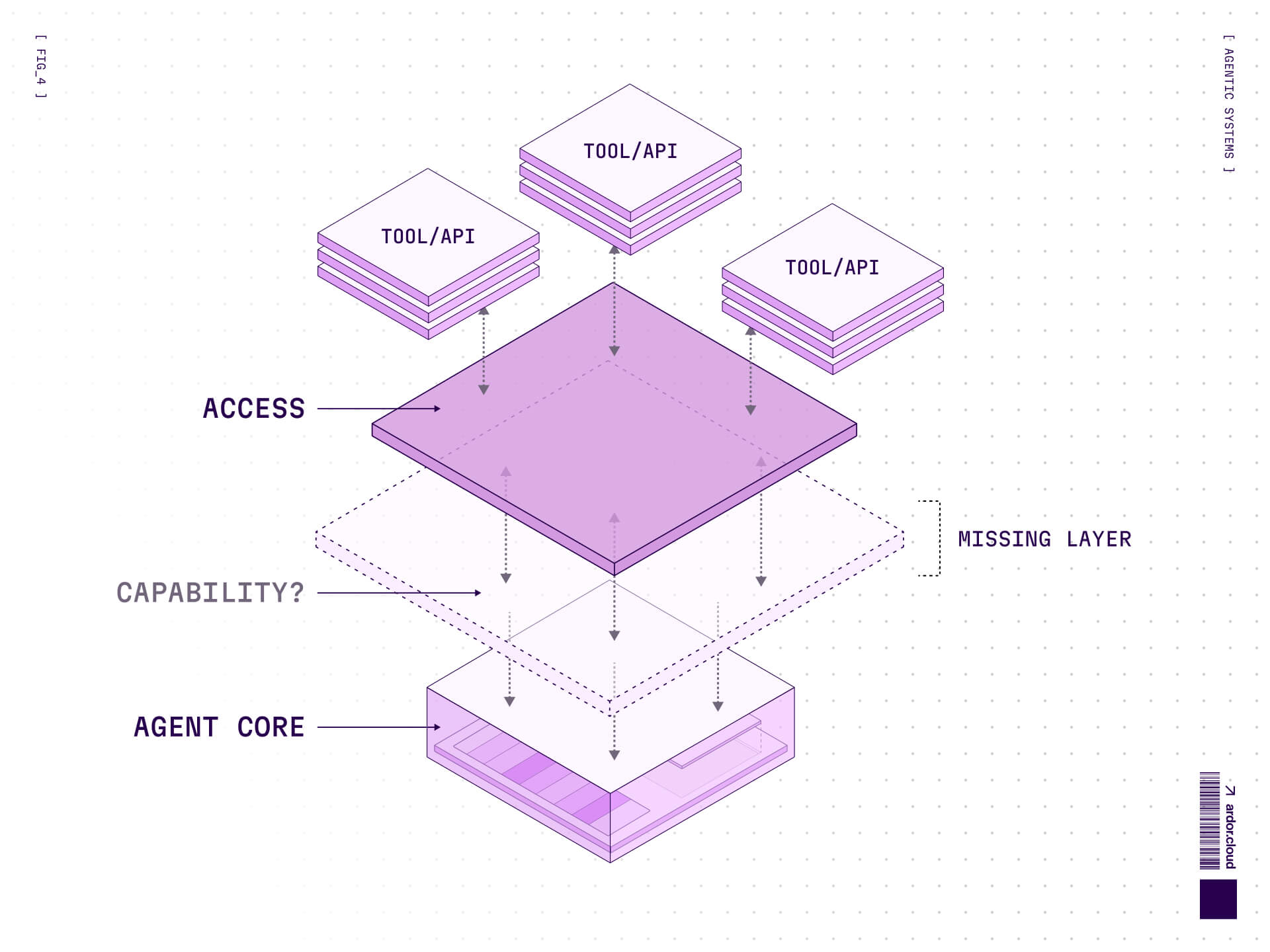

The Missing Layer: Capability vs Access

There's a conceptual distinction that the industry missed for too long: access to tools is not the same as capability to use them effectively.

MCP gave us access. It standardized how agents connect to external systems. But connection isn't competence. An agent with access to a Docker API isn't automatically good at container orchestration. An agent with access to a database isn't automatically good at query optimization.

The stack looked like this:

Tools (bottom layer): Raw capabilities—APIs, CLIs, databases

Workflows (middle layer): Sequenced tool invocations—scripts, pipelines

Judgment (top layer): Missing—knowing when, how, and why to use tools

That missing top layer is where agents actually become useful. It's the difference between giving someone a toolbox and teaching them carpentry. MCP gave us the toolbox. We needed the training.

This is where skills enter the picture.

Phase Two: Skills

What Skills Are

A skill is a packaged unit of agent capability. Not just "here's a tool you can call," but "here's how to use this tool effectively, when to use it, what to watch out for, and how to verify success."

The structure is deceptively simple:

That SKILL.md file is doing heavy lifting. It's not just documentation—it's transferable expertise. It contains:

Context: What this skill does and when to use it

Patterns: Proven approaches for common scenarios

Guardrails: Known failure modes and how to avoid them

Examples: Concrete demonstrations of success

When an agent loads a skill, it's not just getting access to a capability—it's getting accumulated wisdom about how to actually use it.

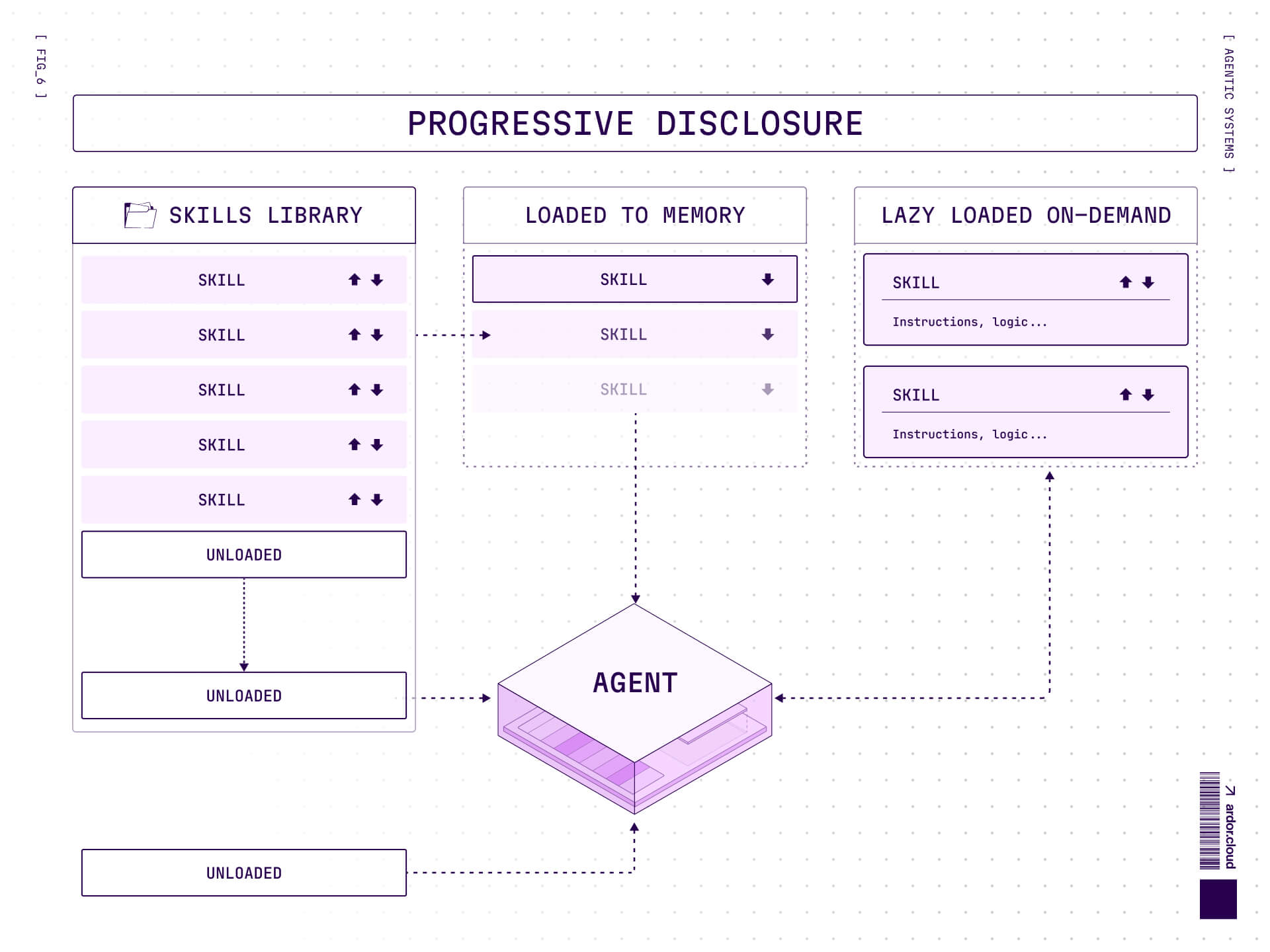

Progressive Disclosure

Here's the clever part: skills use progressive disclosure to avoid recreating the monolithic prompt problem.

An agent doesn't load every skill at once. The system works in stages:

Metadata only: What skills exist, what they do (minimal tokens)

Full instructions: Load the complete SKILL.md when needed (targeted token spend)

Code execution: Run associated scripts only when required (zero context cost until execution)

This is fundamentally different from MCP's "here's every tool you might possibly need" approach. Skills are lazy-loaded capabilities. The agent discovers what exists cheaply, then pays the context cost only when specific capabilities are required.

Research on context management in LLMs shows that progressive disclosure and selective context loading can dramatically reduce unnecessary context usage while maintaining task performance. The token efficiency gains are substantial.

This isn't just an optimization—it's what makes skills viable at scale.

Why Skills Solve MCP's Problems

Let's be concrete about the architectural differences:

MCP-heavy system:

All tool schemas loaded upfront

Protocol overhead in every message

Reasoning space consumed by connectivity

Limited compositional depth before context exhaustion

Skill-driven system:

Skill metadata loaded minimally

Full context loaded on-demand

Reasoning space preserved for actual work

Compositional depth limited by task complexity, not protocol overhead

The token economics are radically different. An MCP server might consume 2-3K tokens per tool in schema definitions. A skill consumes 50-100 tokens in metadata until actually invoked, then loads its full context (typically 1-2K tokens) only when needed.

More importantly, skills are reusable in a way MCP tools aren't. When you write an MCP tool, you're creating a connection point. When you write a skill, you're capturing expertise that any agent can apply. Skills compose vertically (deep capability) while MCP composes horizontally (broad connectivity).

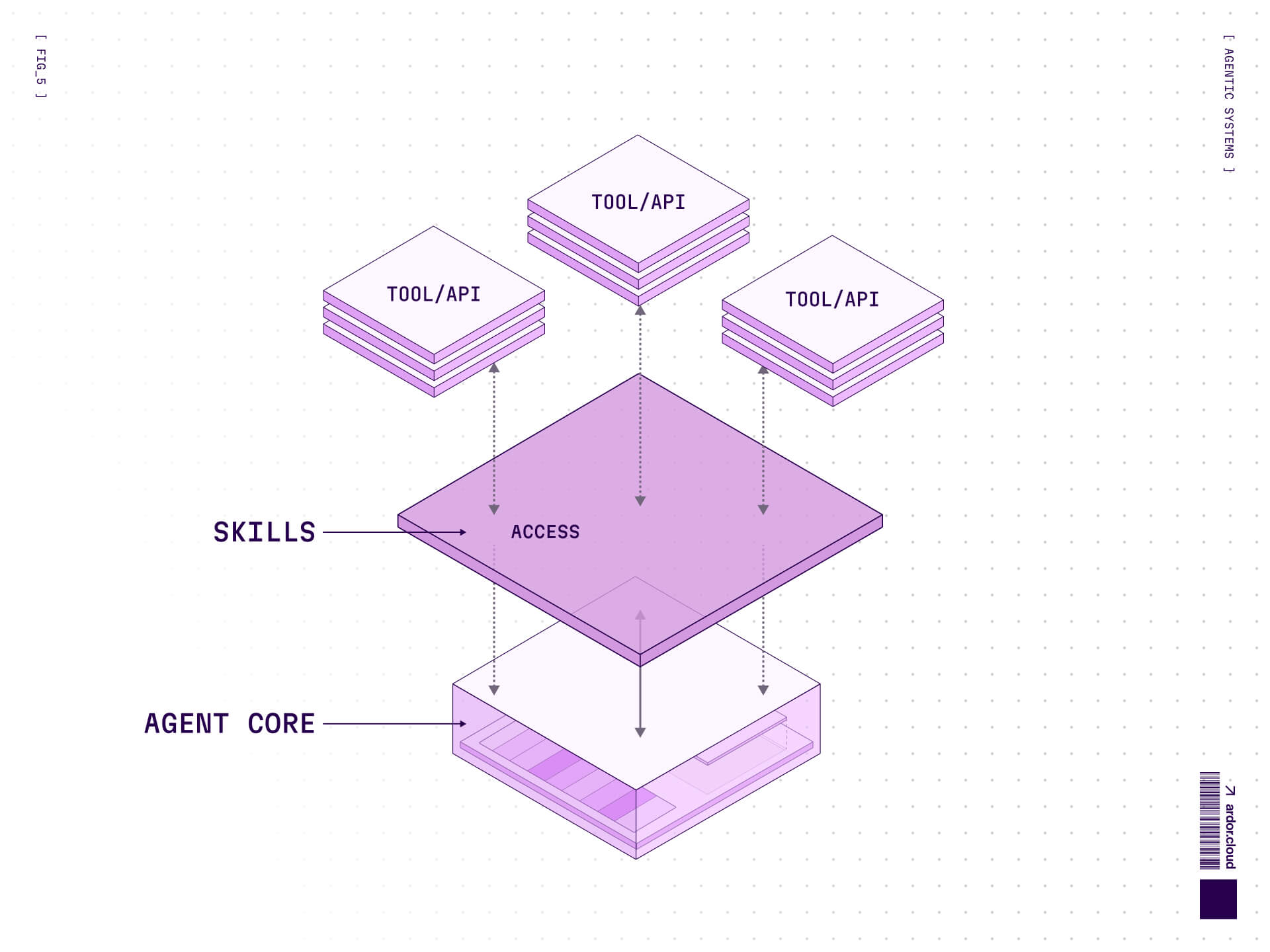

The right answer isn't "skills instead of MCP." It's skills on top of MCP. MCP handles the plumbing. Skills handle the intelligence.

Skills in Context

Skills vs MCP

This is critical to understand: skills and MCP aren't competing approaches. They're complementary layers in the stack.

MCP = horizontal integration layer (how do I connect to systems?)

Skills = vertical capability layer (how do I use those systems effectively?)

An MCP server might expose database operations: connect, query, update, migrate. A skill teaches the agent database engineering: when to denormalize, how to optimize queries, when to add indexes, how to handle connection pooling.

The MCP server gives you the verbs. The skill gives you the grammar.

This matters for ecosystem development. MCP's value is in ubiquity—the more systems that speak MCP, the more valuable the protocol becomes. Skills' value is in specificity—the better a skill captures domain expertise, the more useful it becomes.

You want thousands of MCP servers. You want dozens of exceptionally good skills.

Skills in Software Development

Engineering Failure Surfaces

Software development is where naive agent architectures go to die. There are too many failure surfaces, too many edge cases, too many domains where surface-level knowledge fails catastrophically.

Consider the typical failure points in a modern SDLC:

CI/CD: Environment configuration, secret management, dependency resolution

Infrastructure: Resource provisioning, networking, monitoring setup

Debugging: Log analysis, performance profiling, distributed tracing

Deployment: Blue-green deployments, rollback procedures, health checks

An agent with raw tool access to these systems will fail reliably. It'll configure CI without understanding cache invalidation. It'll provision infrastructure without considering blast radius. It'll deploy code without proper health checks.

CI/CD configuration remains a major source of engineering bottlenecks for development teams. This isn't because the tools are hard to access—it's because the knowledge of how to configure them correctly is specialized and hard-won.

This is precisely where skills shine.

Turning Agents into Engineers

A well-designed skill for CI/CD doesn't just explain "here's how to write a GitHub Actions workflow." It encodes engineering judgment:

When to cache dependencies (and when caching causes more problems than it solves)

How to structure jobs for parallelization

What belongs in CI vs what belongs in pre-commit hooks

How to handle secrets across different deployment environments

When to fail fast vs when to retry

This transforms the agent's interaction model. Instead of:

You get:

The skill provides checkpoints. The agent knows what good looks like at each stage. When something fails, the skill contains debugging protocols. When edge cases emerge, the skill has seen them before.

This is what lets agents ship production software instead of just writing code.

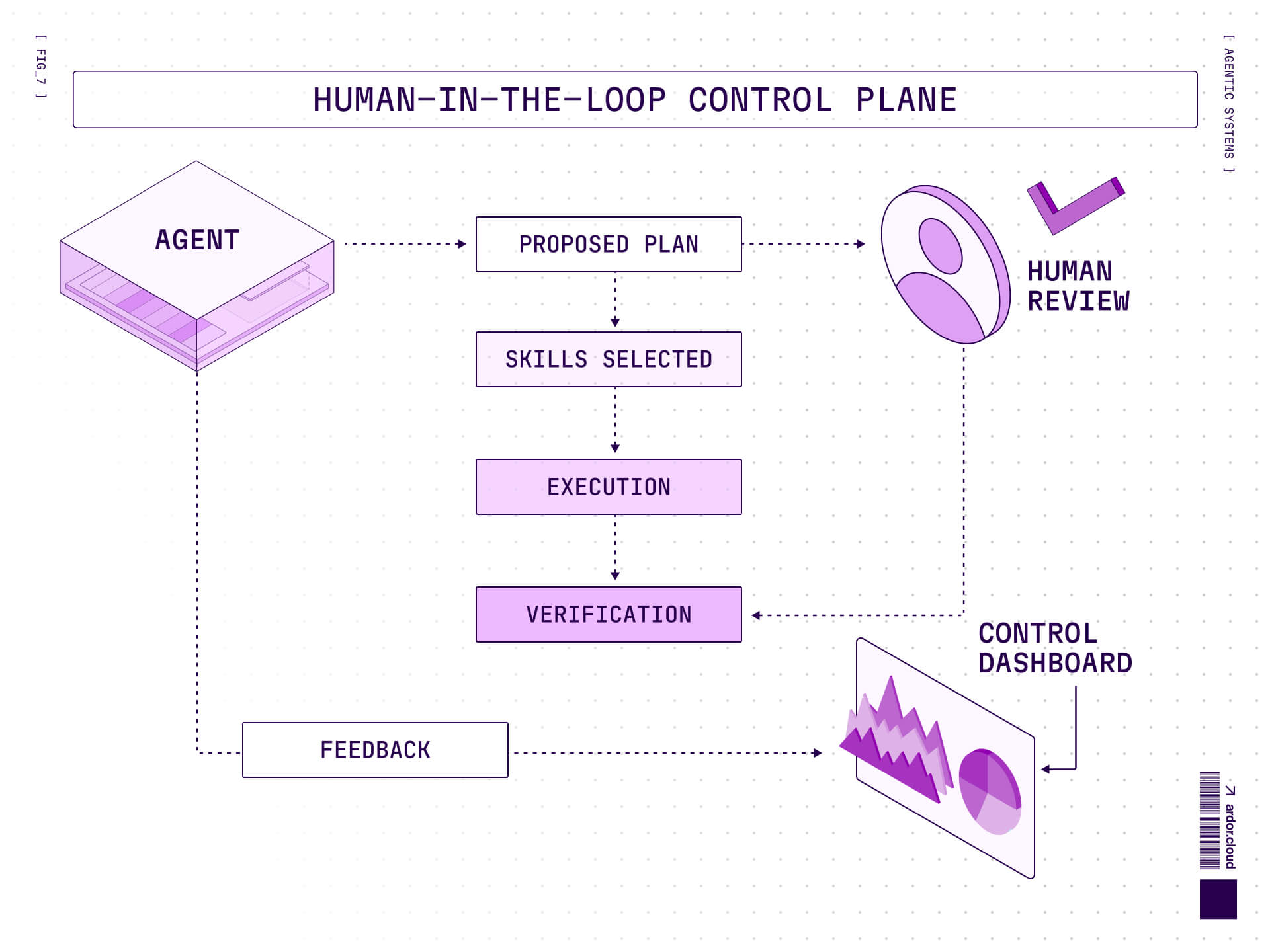

Human-in-the-Loop

Here's an uncomfortable truth about agent autonomy: full autonomy isn't what most organizations want, especially in production environments.

What they want is augmented agency—agents that can execute complex workflows autonomously, but with human judgment in the loop at critical decision points.

Skills make this tractable. A well-structured skill defines natural intervention points:

Proposal phase: Agent generates a plan, human approves/modifies

Execution phase: Agent runs deterministic operations autonomously

Verification phase: Agent checks results, escalates anomalies

Feedback phase: Human corrections feed back into skill refinement

This isn't a concession to technological limitations. It's sound engineering. Research from Microsoft on human-AI collaboration shows that hybrid systems with clear handoff points consistently outperform both pure automation and pure human execution.

The control plane is part of the architecture. The agent proposes, the human approves or overrides, and the feedback loop continuously refines the skill itself. This creates a system that gets more capable over time, not through better models (though that helps), but through accumulated operational wisdom.

For enterprise adoption, this is often the deciding factor.

Skill Lifecycle

Skills aren't static. They're living systems that evolve with usage. The lifecycle looks like this:

Author → Validate → Deploy → Observe → Update

Each phase matters:

Authoring: Capture expert knowledge in SKILL.md format

Validation: Test against real scenarios, edge cases, failure modes

Deployment: Make available to agent runtime with proper versioning

Observation: Instrument skill usage, track success rates, identify drift

Updates: Refine based on observed failures and new patterns

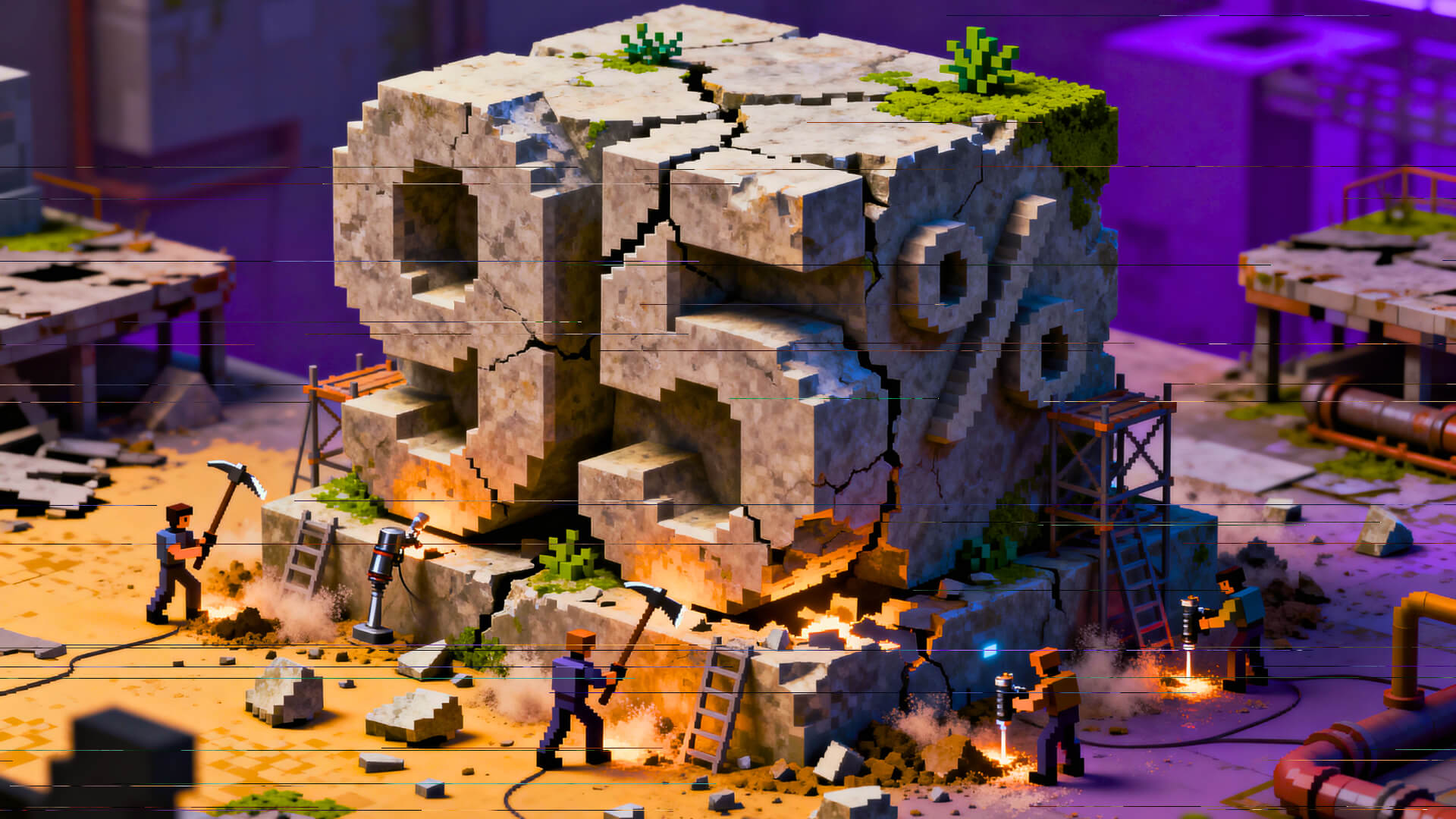

Drift is the silent killer of agent reliability. Your database skill works perfectly until the schema changes. Your deployment skill works perfectly until the infrastructure team migrates to a new orchestration platform. Your debugging skill works perfectly until log formats change.

Infrastructure drift and configuration changes cause a significant portion of unexpected production incidents. Skills that don't account for drift will accumulate silent failures until they're worse than useless—they're confidently wrong.

The solution is observability built into the skill system itself. Track:

Skill invocation patterns

Success vs failure rates

Retry counts and fallback usage

Drift indicators (unexpected errors, novel edge cases)

This transforms skills from static artifacts into adaptive systems. When a skill starts failing more often, that's signal. When fallback paths activate frequently, that's signal. When retry logic kicks in regularly, that's signal.

Treat skills like production services. Because in an agentic system, they are.

Measuring Skill Effectiveness

If you can't measure it, you can't improve it. Skill effectiveness requires metrics, not intuition.

The baseline metrics:

Success rate: How often does skill invocation achieve intended outcome?

Retry count: How many attempts before success (or final failure)?

Fallback usage: How often do we fall back to human intervention?

Confidence vs correctness: Is the agent's confidence calibrated to actual accuracy?

That last one is subtle but critical. An overconfident agent that silently ships broken code is worse than an underconfident agent that asks for help. Calibration matters.

LLMs are often poorly calibrated out of the box—they express high confidence even when wrong. Skills can compensate by providing ground truth checks and validation steps that catch confident mistakes.

The sophisticated version of skill metrics includes:

Task completion time: How long from invocation to verified success?

Token efficiency: How much context did we consume achieving this outcome?

Error recovery: When things fail, how gracefully do we recover?

Knowledge transfer: Are failures creating better skills through feedback?

This moves the conversation from belief ("I think this agent is good at deployments") to evidence ("This deployment skill has a 94% success rate across 500 invocations with an average of 1.2 retries").

Evidence builds trust. Trust enables adoption.

Security & Supply Chain Risk

Skills execute code. They access systems. They make changes. This creates a security surface that requires serious attention.

The threat model is straightforward: if an attacker can inject malicious logic into a skill, they can leverage the agent's permissions to move laterally, exfiltrate data, or cause operational damage. Skills are essentially privileged automation, and privileged automation requires sandboxing and permission boundaries.

The architecture should enforce:

Execution isolation: Skills run in sandboxed environments with defined resource limits

Permission scoping: Skills declare required permissions; runtime enforces least privilege

External access controls: Network access, file system access, API access all require explicit grants

Audit logging: Every skill invocation, every external call, every state change gets logged

Supply chain vulnerabilities and excessive agency are critical risks in LLM applications. Skills that execute arbitrary code without sandboxing are essentially giving attackers a direct path to production.

This isn't theoretical. When you're building agentic SDLC systems, skills have access to:

Source code repositories

CI/CD pipelines

Infrastructure provisioning systems

Production deployment mechanisms

Observability and monitoring tools

The blast radius of a compromised skill is enormous. Security can't be an afterthought.

The good news: because skills are packaged, versioned, and explicitly loaded, you can build proper security controls. Treat skills like containers: signed, scanned, permission-scoped, and audited.

Infrastructure Implications

Supporting skills well requires real infrastructure. This is what separates actual agentic platforms from "agent wrappers"—those thin layers that just orchestrate API calls to foundation models.

A production-grade agent runtime needs:

File system management: Skills reference files, create artifacts, read configurations. The runtime needs isolated, managed file systems per agent instance with proper cleanup.

Sandbox execution: Skills run code. That code needs CPU, memory, and I/O resources. The runtime needs container-level isolation with resource limits and monitoring.

Execution engine: Skills don't just call APIs—they execute scripts, run builds, analyze outputs. The runtime needs a secure execution environment that can handle arbitrary computation.

Observability layer: Every skill invocation, every file operation, every external call generates telemetry. The runtime needs structured logging, metrics collection, and trace correlation.

This is non-trivial infrastructure. It's why most "agent platforms" don't actually support skills properly—the operational complexity is high, and the engineering investment is substantial.

But it's necessary. Production AI systems require substantially more infrastructure sophistication than inference-only systems. Agentic systems push that even higher because they're not just predicting—they're acting.

At Ardor, we treat the skill runtime as first-class infrastructure. It's not an afterthought bolted onto a chatbot—it's the foundation of how agents operate. The runtime provides:

Isolated execution environments per skill invocation

Comprehensive observability with skill-level tracing

Permission boundaries enforced at the infrastructure layer

Built-in rollback and recovery mechanisms

This isn't glamorous work. It's plumbing. But it's the plumbing that makes the difference between demos and production.

When NOT to Use Skills

Credibility requires restraint. Skills aren't always the answer.

Don't use skills when:

The task is simpler than the skill overhead (calculating a sum doesn't need a "math skill")

The capability is already well-captured in model training (code generation for common patterns)

The task is genuinely novel with no accumulated wisdom (exploring entirely new problem spaces)

The cost of skill maintenance exceeds the value of standardization (one-off tasks)

The decision tree is straightforward:

Low complexity + high frequency → Consider a skill for consistency

Low complexity + low frequency → Skip the skill, just solve it directly

High complexity + high frequency → Definitely use a skill

High complexity + low frequency → Judgment call based on reusability

Skills work best when you're solving the same class of problems repeatedly, even if the specific instances vary. Deployment is always deployment, even if each service has unique requirements. Debugging is always debugging, even if each bug is novel.

When every task is truly unprecedented, skills don't help. But in software development, very little is truly unprecedented. Most problems are variations on patterns you've solved before.

That accumulated pattern knowledge is what skills capture.

Do Skills Survive Better Models?

This is the question that makes everyone nervous: won't better foundation models make skills obsolete?

The answer is nuanced. Better models will reduce the need for some skills—the ones that primarily compensate for model weaknesses. If GPT-5 is better at database query optimization than GPT-4, you might not need a database skill that explains query optimization basics.

But skills aren't just compensating for model limitations. They're capturing domain expertise and organizational context that no foundation model will have.

Consider three categories:

Model-compensating skills: These cover gaps in model capability (basic error handling, simple validation). Better models erode their value.

Domain-encoding skills: These capture specialized knowledge (company-specific infrastructure patterns, regulatory compliance requirements). Better models don't affect their value.

Judgment-embedding skills: These encode decision-making frameworks (when to scale up vs optimize, how to balance velocity vs safety). Better models might execute these better, but they still need the framework.

The relationship isn't "skills vs models"—it's "skills amplify models." A better model makes the same skill more effective because it can apply the encoded knowledge more reliably.

Think of it as slope vs ceiling. Skills increase the slope of what you can accomplish as models improve. They don't change the theoretical ceiling of model capability, but they radically improve how close you get to that ceiling in practice.

Research shows that structured knowledge frameworks (what we're calling skills) improve both human and AI performance independently. The combination is multiplicative, not additive.

Skills will evolve. They'll become more sophisticated. Some will become obsolete. But the pattern of packaging transferable expertise for agents? That survives because it addresses a fundamental need: bridging the gap between general intelligence and specific competence.

Organizational Reality

Here's where theory meets practice: skills create organizational challenges that pure technical solutions can't solve.

The question of ownership is immediate and contentious:

Platform team: "Skills are infrastructure, we own infrastructure" Product team: "Skills encode product logic, we own product"

Domain teams: "Skills capture our expertise, we should own them"

All three are partially right. The resolution requires organizational clarity:

Core skills (infrastructure, SDLC, security) → Platform team

Domain skills (ML workflows, data pipelines, business logic) → Domain teams

Integration skills (cross-cutting concerns) → Joint ownership with clear interfaces

The real challenge is governance. Skills affect agent behavior across the organization. Bad skills create incidents. Outdated skills create silent failures. Conflicting skills create inconsistent behavior.

Organizational factors are the primary blocker for AI initiatives, not technical capabilities. When skills are treated as "someone else's problem," they become no one's responsibility.

The successful pattern we've seen:

Skill registry: Centralized catalog of available skills with ownership, documentation, metrics

Contribution process: Clear path for creating, validating, and publishing skills

Review gates: Quality standards before skills become available to agents

Deprecation policy: Lifecycle management for skills that are outdated or redundant

This is boring governance work. It's also where agent initiatives live or die. You can have the most sophisticated skill system in the world—if the organization can't agree on who owns what, nothing ships.

Ecosystem & Standards

The current state is fragmented. Every agent platform has its own skill format, its own loading mechanism, its own runtime expectations. This is early-ecosystem chaos, and it's holding back the technology.

What we need is convergence on:

Skill format standards: Common structure for SKILL.md, metadata schemas, dependency declaration

Skill registries: Shared repositories where skills can be discovered, versioned, and distributed

Runtime compatibility: Agreement on minimum requirements for skill execution environments

Security standards: Common approaches to sandboxing, permissions, and audit logging

The analogy is containerization. Before Docker, everyone had their own packaging format, their own isolation mechanism, their own deployment process. Docker didn't invent containers—it standardized them. The standardization enabled the ecosystem.

Skills need their Docker moment.

The Model Context Protocol is positioning itself as this kind of standard, and there's value in that approach—but MCP is focused on connectivity, not capability. We need skill-specific standards that complement MCP's protocol-level standardization.

At Ardor, we're building with this future in mind. Our skill format is designed to be portable. Our skill registry is designed to be federable. Our runtime is designed to be compatible with emerging standards.

Because here's the insight: skills are too valuable to remain proprietary. The more agents that can use the same skills, the more valuable those skills become. The more platforms that support a common skill format, the larger the ecosystem of skill authors.

Network effects matter. The platform that fragments the ecosystem might win in the short term. The platform that unifies it wins long term.

Ardor POV

At Ardor, we didn't add skills as a feature. We built the entire platform around skills as first-class primitives.

Our architecture:

Skills define capabilities: What agents can do is directly determined by loaded skills

Orchestration leverages skills: Multi-agent workflows compose skills, not raw tools

Infrastructure supports skills: Our runtime is designed for skill isolation and observability

Feedback refines skills: Operational data continuously improves skill effectiveness

This isn't a differentiated feature set—it's a differentiated architecture. When you prompt Ardor to build a full-stack application, here's what actually happens:

The orchestration layer identifies required capabilities (frontend, backend, database, deployment)

The skill system loads relevant skills (React patterns, API design, schema design, CI/CD)

The execution engine runs skill-guided workflows with built-in verification

The observability layer tracks what worked, what failed, and why

The feedback loop updates skills based on real-world performance

Every layer is skill-aware. We're not bolting skills onto an existing agent framework—we're building an agentic SDLC platform where skills are the fundamental abstraction.

This is why we can ship production-grade applications from prompts. Not because our models are better (we use the same foundation models everyone else does). Not because our prompts are more clever (prompt engineering has diminishing returns). But because we've encoded engineering expertise into skills that agents can reliably apply.

When Ardor's agents set up CI/CD, they're not guessing based on token predictions. They're applying a rigorously tested CI/CD skill that encodes years of DevOps expertise. When they design databases, they're using schema design skills built from analyzing thousands of production systems. When they handle deployments, they're following deployment skills refined through operational feedback.

The result: agents that don't just write code, but ship software. That's the difference skills make.

Closing: The Evolution Continues

The progression is clear now:

Monolithic prompts → Couldn't scale beyond demos

MCP → Solved connectivity, created new bottlenecks

Skills → Solved capability, enabled production

Agentic SDLC → The destination, not the journey

We're still early. Skills are in their container-pre-Docker phase—lots of experimentation, not enough standardization, too much fragmentation. But the direction is clear.

The teams that figure out skills will build agents that ship. The teams that treat them as an afterthought will build agents that demo well and fail in production. The gap between those two outcomes is the entire point of this article.

Skills aren't the final answer. They're the current answer—the best pattern we've found for giving agents production-grade capability without drowning them in context. When better abstractions emerge, we'll use those. But right now, if you're trying to ship agentic systems, skills are how you bridge the gap between what models can do and what your organization needs them to do.

The demo worked. Now let's ship it.